Hi everyone,

The following is my conversation with Adam Mead, author of The Complete Financial History of Berkshire Hathaway. We talked about conglomerates, early entrepreneurial experiments at Berkshire, the lean years in the insurance business, managing the company as an informed observer, and returns on his acquisitions.

As to finding another Berkshire, Adam was skeptical:

“I'll never say never, but it would be highly unlikely to find another [Berkshire Hathaway]. You have a Lollapalooza, to use a Charlie Munger term, starting when they're able to shoot fish in a barrel.”

You can listen to this conversation on Spotify, Apple, anchor (and via RSS).

Disclaimer: I write and podcast for entertainment purposes only. This commentary reflects the personal opinions of myself and my guest. This is not investment advice.

Acquisitions: going-in returns vs. reinvestment

This is another chart from the book worth highlighting. Berkshire was not built on finding extreme outlier deals. Much depended on how capital was reinvested subsequently (whether in organic growth, further acquisitions, or public markets) and, of course, cheap leverage from insurance float.

From the book: “In Berkshire’s early years, good companies were available for bargain prices. It bought the Illinois National Bank & Trust Company and The Buffalo News at book value, and the discarded Scott Fetzer and Fechheimer at premiums that still produced going-in pre-tax returns in the mid-20% range.

Generally, the better the business was, the higher its price (as represented by purchase multiple paid compared to the company’s underlying value). The return on capital of the underlying businesses (the company-level return) ranges widely.

See’s was one of Berkshire’s earliest purchases and was made when markets were not as efficient. The low Scott Fetzer and Fechheimer purchase multiples reflected that Berkshire could act as a safe port amid the leverage buyout storm of the mid-1980s.

By contrast, Lubrizol and Heinz were excellent companies earning great returns on capital, but the price Berkshire paid reflected the market’s correct appraisal of that fact.”

(I didn’t see it specified on the page but I think the numbers refer to return on equity and price/book).

From the conversation: “You have this dynamic in the early days of finding really good businesses like See’s and having a pretty modest multiple. Good businesses at really good prices. Then you have the later days of buying really good or pretty good businesses at higher multiples because the market's just gotten efficient over time. But you still have the dynamic of reinvestment going on.

Let's just use a plain example. If you had a business earning 30% on capital and you paid two times that capital, your going in return would be 30 divided by two, 15%. The important part is, if that business can grow, you don't have to reinvest at 2x the capital, you get to reinvest at 1x. That marginal capital gets, in this example, reinvested at 30%. That drags up your going in return over time. But I think Buffet's very clear in pointing out that you can't pay too much for growth. You can't have a going-in return of 2-3%, even if it grows enormously. The time value of money just destroys any kind of return that you have.

I think he always looks for the good business and then he has a secondary analysis of what are the reinvestment opportunities. And he's fine, as long as the purchase price reflects it, he's fine taking the dividends and finding another place for them. And if the business can reinvest that capital, let's do that. That plays out in the extreme case of the energy business, where you're still getting, in many cases, 11-12% regulated return, which is nothing to sneeze at.”

Conglomerates before Berkshire

“The first sort of real conglomerate was American Home Products in the late 1930s. I do have some of those Moody’s reports on my website.

They weren't crooks. I think that can kind of be misconstrued. These guys weren't the Enrons of their day trying to just put something over on investors. But they strayed a little bit in terms of messing around with the accounting or saying, gee, the market's valuing our conglomerate at 20 times earnings or 15 times earnings, and we're gonna buy this other company at five or six times earnings. And I can buy anything that I want as long as it's less than my P/E. And it's gonna magically transform my conglomerate into something better. Now the problem with that is it ignored the underlying economics.”

Control vs. delegation

“I think this whole idea of extreme delegation comes from the fact that Buffet and Monger started as stock pickers. What is the difference between owning a 5% position and owning a hundred percent position? You have the ability to direct the actions of that company. But should you? Berkshire was being almost agnostic in the sense of ownership level. We're still gonna let that manager run his or her business. We're only attracted to businesses that are good anyways. So why would we go in and meddle?”

“You don't just have delegation just shy of abdication. It's hands-off in the sense of not meddling, but you still have an informed observer. That is the key. Buffet's getting fed this river of data coming into Omaha. And I think he communicates his thinking to managers through his questions. Okay, let's be a little bit more aggressive in trying to price the product because we think we have pricing power.”

“Buffet writes a letter to Chuck Huggins [at See’s Candy] and says, I just went out and I saw this one store and our candy was sitting next to Russell Stover, and it was kind of a mess. Let's use these psychological tricks to keep our candy front of mind and make it have apparent scarcity. I mean, that's Buffet the entrepreneur, that's Buffet the manager.”

Buffett’s early days at Berkshire

“He began in 1965 at Berkshire Hathaway. He lived in Omaha and a guy like that, so attuned to business, is going to just be curious about all these businesses around him. Well, one of them was National Indemnity. This was the real first big deal of Berkshire Hathaway, 1967. He bought National Indemnity and its sister company, National Fire and Marine for $8.6 million. In hindsight, he said he would've been better off buying that in an entity outside of Berkshire Hathaway.

So it was sort of a mistake on his part to bring the legacy Berkshire Hathaway shareholders along with him. He just used it as his vehicle and the rest is history. That was the first transformative deal based. That gave Buffet not only a platform to invest the float, which was almost $20 million. Jack Ringwalt, the manager of that business, showed him that you can [underwrite] any risk as long as it's priced appropriately.”

The lean years in insurance

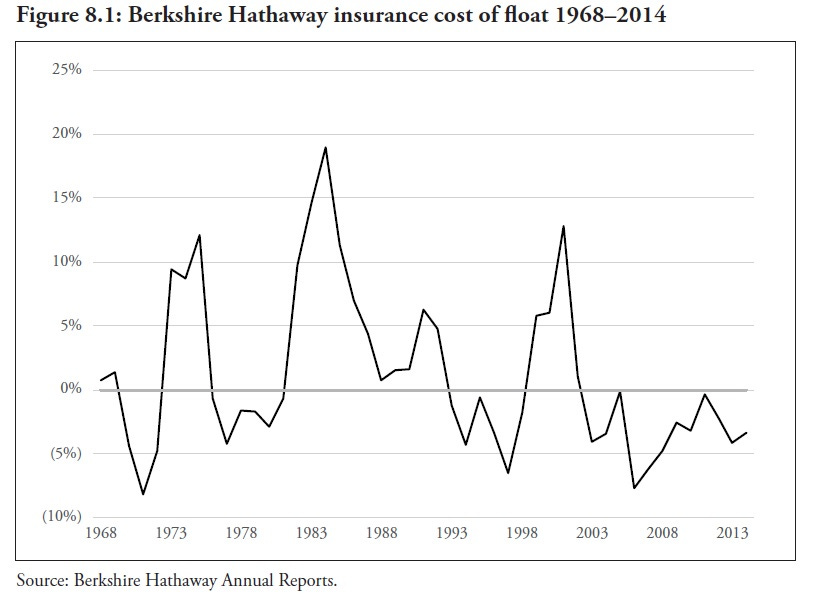

Another takeaway from both the letters and Adam’s book is the number of years that parts of the insurance struggled. Early expansion efforts weren’t always successful. And in the early 80s the competitive environment was very challenging. While the long-term cost compares favorably to even government debt, shareholders had to maintain conviction for a long time.

“You have Buffet taking this idea that insurance can be a very good business, just trying to see what works. Let's scale this thing, right? … Some of these ultimately failed. This is experimentation and you have to see what works. Different markets operate differently. That was the 1970s, this period of let's build this thing.

From 1982 to 1992, they lost $522 million from underwriting alone. Now, it sounds like a lot, and it was, but the insurance business overall was profitable because of the investment income. There was a period, National Indemnity saw its premiums decline from the mid eighties to the late nineties. Something like $350 million to $50 million. Just an extreme decline. That's a long time.”

🎙Adam Mead, Author of The Complete Financial History of Berkshire Hathaway