Bill Miller’s Journey (Part II): Lessons of Triumph and Tragedy.

“It is different every time. The relevant analytical exercise is to figure out what the differences are, what it all means, so that one can make sensible investment decisions.”

This is the second part of my Bill Miller profile. To understand his evolution and style as an investor, check out part I.

In March 2002, in the middle of the dotcom bust, Bill Miller reminisced on the last bear market. “I took over sole management of the fund in November 1990,” he wrote. “The economy was in recession, stocks were down, banks — our largest industry concentration — were failing, Saddam Hussein occupied Kuwait, and oil had spiked to about $40 per barrel. It was clearly a terrific time to invest.”

This past October, Miller remarked that “nothing” worried him because the market spent an “inordinate amount of time worrying,” and time was better expended on making good long-term investment decisions. This was typical of Miller, who liked to assert that “the path of least resistance for the stock market is higher.” Most of the time, he was correct. But between 2002 and 2021 lay the greatest failure of his career. At the point of his most assets under management, the eternal long-term optimist failed to recognize that the ground had shifted beneath his feet.

I’ve been fascinated with Miller’s life and career. He has a lot to teach about investing and navigating an uncertain and changing world. Miller stuck to his principles but evolved his strategy during his run of beating the market 15 years in a row. But he failed to see crucial differences between his past experiences and the housing crisis of the mid-2000s and ended up as one the era’s biggest losers. Through it all, the ups and the downs, Miller generously shared his thoughts, reflections, and frank self assessments in his letters. In this, the second part of a two-part series, I let him mostly speak for himself. If a quote isn’t attributed, it’s his.

In the first part I wrote about Miller’s successful transition from traditional value investing to investing in technology companies. We explored his multi-disciplinary approach and how he was influenced by the science of complexity at the Santa Fe Institute. At the end of the dotcom bubble, Miller recognized a shift in the market and reduced his exposure to technology. Fortunately, his other favorite group, “the long-lagging financials,” had finally “begun to perk up.”

In this piece we’ll explore Miller’s fondness for averaging down, the run-up to the financial crisis, his very public failure, and his rebound.

Sections:

Lowest cost wins.

Being different.

Deadly muscle memory.

Darkest hour.

Comeback.

The lessons.

Disclaimer: I write for entertainment purposes only. This does not constitute an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to buy any securities or funds or other investments mentioned. Seek your financial, tax, legal, accounting, or other advisor’s advice before making any investment decisions. Do you own work. I am are not your fiduciary or advisor.

Lowest cost wins.

Buying at a discount to intrinsic value remained the cornerstone of Miller’s investment philosophy. He was looking to capitalize on other investors’ short-term time horizons and behavioral or analytical mistakes. Miller believed that timing the market was futile (though he had just made a call on the technology sector) and was happy to buy a stock as it continued to decline.

“If you want to boil down everything we do, it's this: The guy with the lowest average cost wins.”

“Stock prices change far more rapidly than does intrinsic business value,” Miller said during fiscal year 2000. “That’s because prices reflect recent history, current fundamentals, and reasonably foreseeable prospects, those looking out, say, six to nine months, all filtered through the prism of psychology and emotion.”

“What we try to do is find companies whose economic models support returns on capital above the cost of capital, so that they create value at a rate greater than the mere addition to capital that occurs through the retention of earnings in the business. Such companies usually are recognized by the market and valued appropriately, but sometimes they’re available at discounts to intrinsic value. These discounts can arise for many reasons. The most common are macroeconomic change, problems with the company or its industry, or the immaturity of the business. In each case, the long-term economics of the business are obscured by factors or events that prove to be temporary. These temporary factors produce the mispricings that eventually lead to excess returns. One of the most powerful sources of mispricing is the tendency to overweight or over-emphasize current conditions.”

There are numerous examples of out-of-favor stocks that ended up in his portfolio. Miller bought both Dell and AOL in 1996 when the market dumped the shares. That year, he also bought stock in casino operator Circus Circus. The stock fell from the $30s to $12 and Miller “quadrupled his position.” He later added Mirage Resorts and MGM Grand. “The stocks are flat, but the cash flows of gaming companies have been growing,” he explained.

In 1999, he bought shares in McKesson after an accounting scandal. He also added aggressively as shares of Waste Management fell from the $50s to the “low $30s” after yet another accounting scandal. He also invested in two scandal-ridden conglomerates, Tyco and Enron, noting later, “we were right, for example, to buy Tyco under $10 when it was involved in an accounting scandal. We were wrong to buy Enron when it was also involved in such a scandal.”

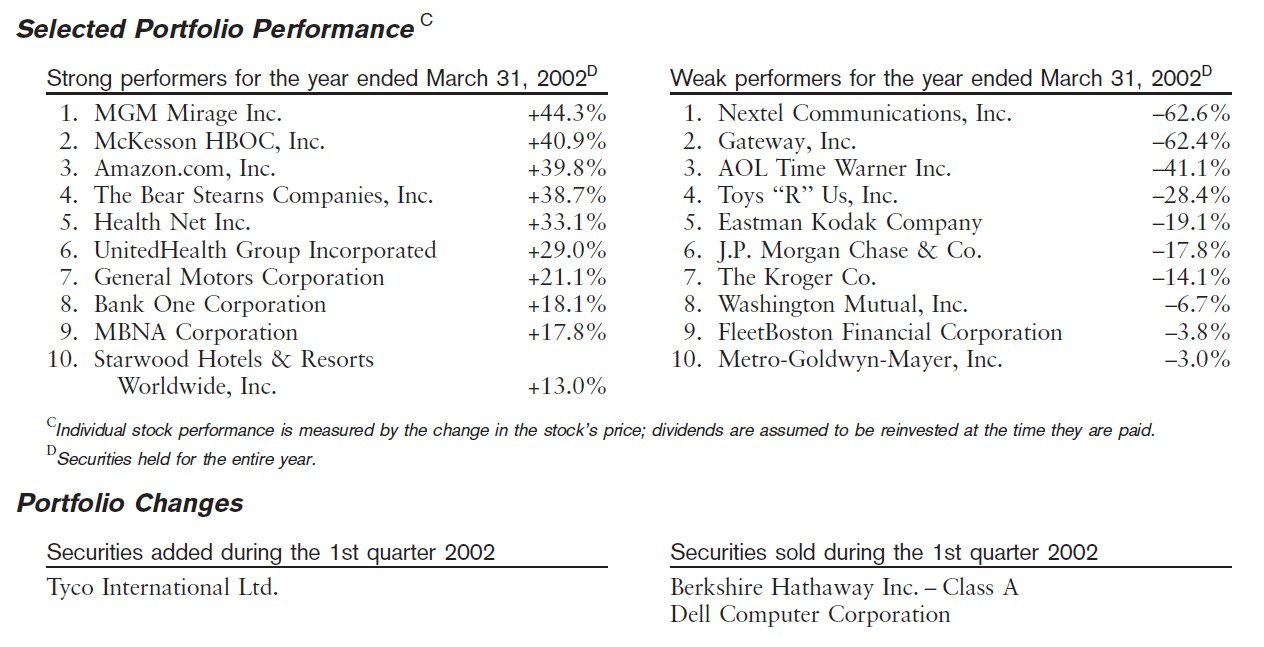

Miller invested in distressed telecom names such as Qwest Communications, Nextel, and fiber provider Corning. Nextel had tumbled from $80 to $9; Corning had dropped from $100 to $10. Money Magazine called his fund the “scariest portfolio ever,” which Miller reprinted in his letter with some pride. Journalists didn’t understand that the fear in his names made them such attractive contrarian bets. Nextel became his largest portfolio holding and Legg Mason became the largest outside owner of Amazon with a 16% stake. Another internet name was Barry Diller’s IAC, with stakes in Expedia and Hotels.com and what Miller called “Warren Buffett-type characteristics” of “high free cash flow, a strong balance sheet, and businesses that arbitrage the economics of various industries.”

Miller later wrote that “factor diversification” had been a key reason for his winning streak. He defined it as owning “a mix of companies whose fundamental valuation factors differ.” The winners and losers of fiscal year 2001 illustrate this. While most of his tech names sold off, old economy stocks in healthcare, gaming, and financial services did well.