Buffett's first major TV interview and 5,106 pages of wisdom

"I don’t have to make money in every game. There are all kinds of things I don’t know about. Too bad. The process is defining your area of competence and finding what sells cheapest in that area."

Hello everyone,

Yesterday, for the first time in two years, Berkshire shareholders returned to their annual pilgrimage to Omaha. I’ve only attended once in 2009. Something about joining tens of thousands of others triggers a contrarian instinct in me (though arguably the alpha of attending is in the connections and serendipity emerging from the meetings leading up to the main event).

Instead, I re-watched one of my favorite Buffett interviews. It is only seven minutes long and was conducted in 1985 by George Goodman, who helped start Institutional Investor magazine and wrote one of my favorite books about Wall Street, The Money Game, under the pseudonym Adam Smith.

In his book Supermoney Goodman wrote about his first encounters with Ben Graham and Buffett. This was in 1970, shortly after the publication of The Money Game. Goodman received a letter from Ben Graham’s summer home in France.

While Goodman had much respect for Graham...

There is only one Dean of our profession, if security analysis can be said to be a profession. The reason that Benjamin Graham is undisputed Dean is that before him there was no profession and after him they began to call it that.

… he also pointed out that Graham’s value investing philosophy seemed to belong to a bygone era of ample bargains. Among Goodman’s social circle of professional investors, Graham’s ideas were “trading at a discount.”

To Graham, a stock had Intrinsic Value. In the Dark Ages of the Thirties, it was not so hard to find Intrinsic Value.

Benj. Graham was studied with respect by generations of analysts, but not with affection. What was one to do all day, if the market was to be ignored? That would not get you rich. How could anybody ignore IBM? How smart could somebody be if he had missed IBM—not because he didn’t know about it, but because he had considered it, measured it and turned it down?

Graham was well aware that he was himself selling at a discount. Through a number of editions of Security Analysis, the final sentence to the “Summary of the Valuation of Common Stocks” warned that “our judgment on these matters is not necessarily shared by the majority of experienced investors or practicing security analysts.”

Graham asked Goodman to work on a new edition of The Intelligent Investor:

“There are really only two people I would want to work on this,” Graham said. “You’re one, and the other is Warren Buffett.”

“Who’s Warren Buffett?” I asked.

By that time, Buffett had just dissolved his partnership and Berkshire Hathaway stock was still traded on the pink sheets.

While Goodman was well connected among money managers in New York and Boston, Buffett was an unknown quantity to him.

All through the sixties, Warren stayed away from the stocks that dominated the financial headlines and provided the excitement in the board rooms. The partners bought an old textile company called Berkshire Hathaway because its net working capital was $19 a share and their cost was about $14; they ended up owning most of the company, and Warren put new management in.

Buffett had eschewed the growth stock craze of the 1960s, a central theme in The Money Game.

What was remarkable was that Buffett was easily the outstanding money manager of the generation, and what was more remarkable was that he did it with the philosophy of another generation.

Just pure Benj. Graham, applied with absolute consistency—quiet, simple stocks, easy to understand, with a lot of time left over for the kids, for handball, for listening to the tall corn grow.

Goodman was wrong about there being much time left for Buffett’s children. But he was rightly captivated by Buffett’s success:

His partnership began in 1956, with $105,000, largely supplied by uncles, aunts and other assorted relatives. It ended in 1969 with $105,000,000, and a compounded growth rate of 31 percent. Ten thousand dollars invested in the partnership in 1957 would have grown to $260,000.

He did not have a committee to deal with, and he did not have a boss. He kept himself out of the public eye, though for most of his career the public eye would not have been on him anyway. If he bought so much of a company that he controlled it, he was willing to step into the business. All of these factors freed him from more typical restraints.

Buffett also shut down his investment partnership at the top of the market. This was incredible to Goodman because it went against the instinct to maximize fee income.

He quoted from Buffett’s letters during the late stages of the ‘68 bull market:

“I am out of step with present conditions. When the game is no longer being played your way, it is only human to say the new approach is all wrong, bound to lead to trouble, and so on . . .

On one point, however, I am clear. I will not abandon a previous approach whose logic I understand (although I find it difficult to apply) even though it may mean forgoing large, and apparently easy, profits to embrace an approach which I don’t fully understand, have not practiced successfully and which, possibly, could lead to substantial permanent loss of capital.”

“Philosophically, I am in the geriatric ward,” he wrote.

“We live in an investment world populated not by those who must be logically persuaded to believe, but by the hopeful, credulous and greedy, grasping for an excuse to believe.”

After several lunches, Goodman visited Buffett in Omaha where they “went over the lessons of the Master to see what was still relevant, like two scholars over the Scripture.”

Goodman was fascinated by the fact that a money manager could succeed this far from Wall Street. He kept asking Buffett about his decision to live in Omaha. I highlighted a quote from this visit in The Reading Obsession:

“I can be anywhere in three hours,” Warren says, “New York or Los Angeles. Maybe a little longer, since they took the nonstop off. I get all the excitement I want on those visits.

I probably have more friends in New York and California than here, but this is a good place to bring up children and a good place to live. You can think here. You can think better about the market; you don’t hear so many stories, and you can just sit and look at the stock on the desk in front of you. You can think about a lot of things.”

During their tour, Buffett introduced Goodman to his philosophy. While Goodman was used to aggressive managers trading stocks, often at an aggressive pace, Buffett emphasized valuation and business analysis. And patience.

After a while, around Warren, you begin to get a feel for business, as opposed to stocks moving.

“Whether the New York Stock Exchange is open or not has nothing to do with whether The Washington Post is getting more valuable. The New York Stock Exchange is closed on weekends, and I don’t break out in hives. When I look at a company, the last thing I look at is the price. You don’t ask what your house is worth three times a day, do you? Every stock is a business. You have to ask, what is its value as a business?”

We are driving down a street in Omaha; and we pass a large furniture store. I have to use letters in the story because I can’t remember the numbers.

“See that store?” Warren says. “That’s a really good business. It has a square feet of floor space, does an annual volume of b, has an inventory of only c, and turns over its capital at d.” “Why don’t you buy it?” I said. “It’s privately held,” Warren said.

“Oh,” I said. “I might buy it anyway,” Warren said. “Someday.”

Berkshire acquired the Nebraska Furniture Mart more than a decade later in 1983.

Despite his track record, Buffett was still not widely followed among professional managers (though he was well known among fellow disciples of Graham). When he started buying shares in the undervalued Washington Post, Goodman paid attention. But the idea did not resonate among Goodman’s money manager friends.

I tried the Washington Post idea on my Wall Street friends. They couldn’t see it. “Big city newspapers are dead,” they said. “The trucks can’t get through the streets. Labor problems are terrible. People get their news from television.” And anyway, it wasn’t the next Xerox.

In the end, neither Goodman nor Buffett worked on a new edition of The Intelligent Investor. “We wrote a note to Ben,” Goodman wrote, “saying his book didn’t really need any improvements.”

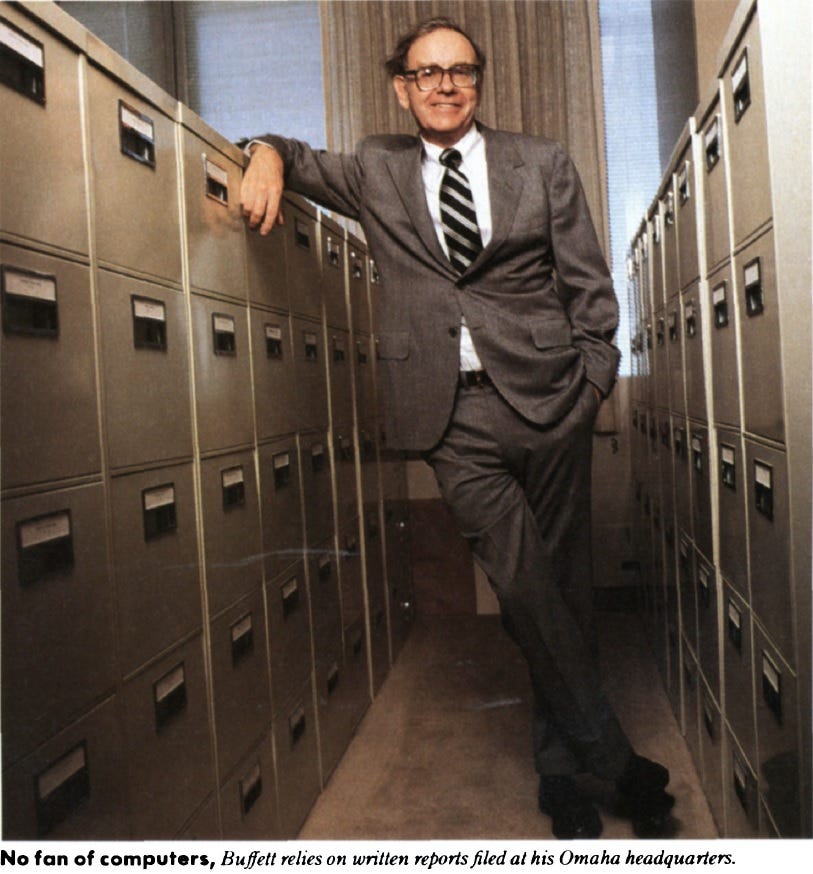

But Goodman managed to interview Buffett more than a decade later, in 1985, for his show “Adam Smith’s Money World.”

“I don’t think Warren has ever been on television until this interview, and he is certainly never courted publicity, but recently he got a lot of it when he emerged as the key figure in the takeover of ABC by Capital Cities.”

(Goodman was wrong - Buffett had appeared on TV at least once before, in 1962.)

His lessons were short, simple, and timeless.

Remember the first rule: don’t lose money

It’s all about temperament

Think for yourself

Buy businesses, not stocks

Reduce the noise

Choose the game that’s right for you

Patience and discipline: simple, not easy

Data can be a distraction

One reason I enjoy Goodman’s interview and his chapter in Supermoney (which you can find here as “Somebody Must Have Done Something Right: The Lessons of the Master”) is that he managed to extract just a handful of quotes that still capture Buffett’s essence. They don’t tell us very much about Buffett’s methods or how he became so successful. But they illustrate clearly how different he was from the portfolio managers that Goodman encountered in his daily work.

And they’re brief. Buffett has been a teacher for decades through his letters, annual meetings, and interviews. The accumulated scripture can be overwhelming. If you’re a junkie, you’ll enjoy this 5,106 page document compiled by @Austinvalue with letters, transcripts, writings, and interviews. I applaud and appreciate the effort of putting it together. I enjoy having it. But I doubt I will ever read it cover to cover.

Go ahead: Download the document. Feel good about having Buffett’s cumulative wisdom on your hard drive. Then watch him for 7 minutes in his prime, be reminded of just one good idea, and go about your day a little wiser.

I’ll share the key quotes below.

Remember the first rule

Warren Buffett: The first rule of an investment is: Don’t lose. And the second rule of investment is: Don’t forget the first rule. And that’s all the rules there are. I mean, if you buy things for far below what they’re worth, and you buy a group of them, you basically don’t lose money.

It’s all about temperament

Goodman: Warren, what do you consider the most important quality for an investment manager?

Buffett: It’s the temperamental quality, not an intellectual quality. You don’t need tons of IQ in this business. I mean, you have to have enough IQ to get from here to downtown Omaha, but you do not have to be able to play three-dimensional chess or be in the top leagues in terms of bridge playing or something of the sort. You need a stable personality. You need a temperament that neither derives great pleasure from being with the crowd or against the crowd because this is not a business where you take polls, it’s a business where you think.

Think for yourself

And Ben Graham would say that you’re not right or wrong because a thousand people agree with you. And you’re not right or wrong because a thousand people disagree with you. You’re right because your facts and your reasoning are right.

Buy businesses, not stocks

Goodman: Warren, what do you do that’s different than ninety percent of the money managers who are in the market?

Buffett: Certainly most of the professional investors focus on what the stock is likely to do in the next year or two and they have all kinds of arcane methods of approaching that.

They do not really think of themselves as owning a piece of a business. The real test of whether you’re investing from a value standpoint or not, is whether you care whether the stock market is open tomorrow. If you’re making a good investment in a security, it shouldn’t bother if they closed down the stock market for five years.

All the ticker tells me is the price. And I can look at the price occasionally to see whether the price is outlandishly cheap or outlandishly high but prices don’t tell me anything about a business.

Business figures themselves tell me something about a business but the price of a stock doesn’t tell me anything about a business. I would rather value a stock or a business first, and not even know the price, so that I’m not influenced by the price in establishing my valuation and then look at the price later to see whether it’s way out of line with what my value is.

Reduce the noise

(But remember that Buffett balanced this with plenty of travel.)

Goodman: Don’t you find Omaha a little bit off the beaten track for the investment world?

Buffett: Well, believe it or not, we get mail here (😭) and we get periodicals and we get all the facts needed to make decisions. And, unlike Wall Street, you’ll notice we don’t have fifty people coming up and whispering in our ear that we should be doing this or that this afternoon.

Goodman: You appreciate the lack of stimulus here?

Buffett: I like the lack of stimulation. We get facts, not stimulation here.

Goodman: How can you stay away from Wall Street?

Buffett: Well, if I were on Wall Street, I’d probably be a lot poorer. You get overstimulated on Wall Street. And you hear lots of things. And you may shorten your focus and a short focus is not conducive to long profits.

And here I can just focus on what businesses are worth. And I don’t need to be in Washington to figure out what the Washington Post newspaper is worth. And I don’t need to be in New York to figure out what some other company is worth. It’s simple… It’s an intellectual process and the less static there is in an intellectual process, really, the better off you are.

Choose the game that’s right for you

In Buffett’s case, much of the game was about buying below intrinsic value. Which requires an ability to come up with a good estimate of value.

Goodman: What is the intellectual process?

Buffett: The intellectual process is defining your level…defining your area of competence in valuing businesses. And then, within that area of competence, finding whatever sells at the cheapest price in relation to value. And there are all kinds of things I’m not competent to value. There are a few that I am confident to value.

Goodman: Have you ever bought a technology company?

Buffett: No, I really haven’t.

Goodman: In thirty years of investing, not one?

Buffett: I haven’t understood any of ‘em.

Goodman: So you haven’t ever owned, for example, IBM?

Buffett: Never owned IBM. Marvelous company. I mean, a sensational company. But I haven’t owned IBM.

Goodman: And so, here is this technological revolution going on and you’re not gonna be a participant.

Buffett: Gone right past me.

Goodman: Is that alright with you?

Buffett: It’s okay with me. I don’t have to make money in every game. I mean, I don’t know what cocoa beans are gonna do. There are all kinds of things I don’t know about, and that may be too bad, but you know, why should I know all about it — haven’t worked that hard on it.

Patience and discipline: simple, not easy

Buffett: In securities business, you literally every day have thousands of the major American corporations offered you at a price that changes daily and you don’t have to make any decision. Nothing is forced upon you.

There are no called strikes in the business. The pitcher just stands there and throws balls at you. And if you’re playing real baseball, and it’s between the knees and the shoulders, you either swing or you got a strike called on you. If you get too many called on you, you’re out.

In the securities business, you sit there and they throw U.S. Steel at 25 and they throw General Motors at 16. You don’t have to swing at any of them. They may be wonderful pitches to swing at but if you don’t know enough, you don’t have to swing. And you can sit there and watch thousands of pitches and finally get one right there where you wanted something that you understand and then you swing.

Goodman: So you might not swing for six months?

Buffett: Might not swing for two years.

Goodman: Isn’t that boring?

Buffett: It will bore most people and certainly boredom is a problem with most professional money managers. If they sit out an inning or two, not only do they get somewhat antsy, but their clients start yelling, “Swing you bum,” from the stands. And that’s very tough for people to do.

Data can be a distraction

Goodman: Warren, your approach seems so simple, why doesn’t everybody do it?

Buffett: Well I think partly because it is so simple. The academics, for example, focus on all kinds of variables partly because… The data is there. So they focus on whether if you buy stocks on Tuesday and sell them on Friday, you’re better off. Or if you buy em in an election year and sell em in other years, you’re better off. Or if you buy small companies. There are all these variables because the data are there. And they learn how to manipulate data.

And as a friend of mine says, to a man with a hammer everything looks like a nail. And once you have these skills, you just are dying to utilize them in some way. But they aren’t important.

If I were being asked to participate in a business opportunity, would it make any difference to me whether I bought it on a Tuesday or a Saturday or an election year or something? It’s not what a businessman thinks about in buying businesses. So why think about it when buying stocks? Because stocks are just pieces of businesses.