Henry Ellenbogen’s Playbook for Durable Growth

"Investing in small-cap growth stocks is an immensely creative process, where creativity and success are defined by the ability to see what others—most market participants—don’t see."

When Henry Ellenbogen took over the $8.6 billion T. Rowe Price New Horizons Fund in 2010, it had a 50-year record of investing in small growth companies. By comparison, Ellenbogen had only nine years of experience as an investor. He combined his experience in internet companies with fund’s broader mandate and invested in companies ranging from Netflix to Vail Resorts. He also created a private investment program to participate in late-stage venture investing and invested in companies like Twitter and Atlassian. By the time left in 2019, the New Horizons Fund had $25 billion of AUM and beaten the market with a total return of 375% (~18.9% CAGR). Today, Ellenbogen runs his own firm, Durable Capital (initially raised $6 billion), and manages $13 billion in public equities plus privates.

These are my notes on his investing playbook after reading his shareholder letters at T. Rowe as well as articles and interviews and listening to his 2020 podcast appearance. All quotes are his unless otherwise attributed.

"I had a science background as an under-graduate, and I started to think that companies are like biological organisms. They are either fundamentally healthy or out of balance. If they are in balance with employees, customers, and shareholders, they can grow and thrive. If not, they can seem like they’re doing well for a time, but eventually they’ll get out of balance."

Performance and chart courtesy of Ycharts.com:

Key Insights

Eliminate the “false dichotomy” of public vs. private market investing: Ellenbogen looks for the best durable growth companies across both public and private markets. He believes in the synergy of having the same team cover both markets.

Real winners are rare: Ellenbogen’s mission is to find the companies that can compound for the long-term. Once he finds one the biggest mistake would be to sell too early. Instead, he is comfortable averaging up and the flexible fund structure allows him to buy more stock after a private investment goes public. This flexibility was part of his pitch when building his private markets franchise, reframing the disadvantageous perception of being a mutual fund and not a venture firm.

Looking for Act II: Ellenbogen looks for growth companies that can have a second act after exhausting the potential of their initial market or product. While this is impossible to predict, he emphasizes management teams that make the necessary investments and create the culture and processes to scale the company long-term. He looks for the intellectual honesty required to effectively navigate difficult transitions.

Example: Vail Resorts

It’s a people business: Investing in private companies is a game of access and relationships. An important piece of Ellenbogen’s pitch is his willingness to stand by founders in tough times.

Example: Netflix

Data-driven investing: Ellenbogen and his team focus on KPIs at their portfolio companies as well as in assessing their own performance.

“Deeply human” investing: Ellenbogen analyzes his investment practice like a business and is thoughtful about the game he plays in a highly competitive market.

Learning the craft

Ellenbogen left Harvard College at age 19 for a stint as Chief of Staff to Representative Peter Deutsch (and was called the "boy wonder of Capitol Hill" by the New York Times). He returned and completed his JD/MBA. In 2001, he joined T. Rowe Price to cover media and internet stocks. Ellenbogen was appointed portfolio manager for the Media and Telecommunications Fund from 2004-09. In 2010, he was made portfolio manager for T. Rowe’s storied New Horizons Fund which he managed until his departure in 2019.

He had a front row seat for the bursting of the dotcom bubble. While the market turned very skeptical of internet companies, Ellenbogen had no scar tissue and could see that the internet was about to upend the media landscape. Despite “obvious misallocation of capital” the investments in capacity during the boom were about to fuel a revolution.

In 2006, he wrote about his investment in Google:

"In contrast to analog distribution, such as radio, TV stations, and cable systems, which are highly regulated, closed systems constrained by geographic boundaries and regulatory franchises, Internet companies compete in an open environment where innovation and quality of product are vital to success."

"Once it builds a market-leading service, the company must relentlessly utilize its scale advantages to improve and innovate at a faster rate than its competition."

And about investing in Tencent in 2005:

“The company was gaining market share in the largest online market in all its core product categories—instant messaging, casual games, and a content portal. Furthermore, Tencent Holdings was demonstrating an ability to leverage its strength in one area into organic growth in related areas. The management team’s focus on long-term financial results was penalized by investors looking at the short term in the second half of 2005, as an investment in product development led to temporarily disappointing margins…”

In 2009, he wrote:

“Our first investment in the company was in the fall of 2005. We visited the company in China with locally based analysts who had been following the company since before its initial public offering. The company stood out from its peers for several reasons: its dominant relationship with users in its 74% share instant messaging business; its success in leveraging this relationship into adjacent businesses in the casual games portal business and entertainment portal—a financial model that provided strong returns on capital while funding innovation; and a management team focused on expanding market share and innovation, not maximizing margins.”

He later called the expansion from an initial core growth market a company’s “second act.”

In 2007, he wrote about his investment in Amazon:

"Over the past three years, Amazon aggressively invested in its platform, customer experience, and new services. The company was penalized by the market. During this period, we examined the underlying investments, modeled the potential opportunities, and marked progress. We came to the conclusion that the investment was prudent and, when combined with the existing franchise, would ultimately produce positive financial returns. … we intend to remain investors as we believe the company will continue to gain share of its market and generate high returns on capital while investing for the future, allowing us to compound wealth at an attractive rate."

In 2009, he picked up on what Nick Sleep called "scale economies shared":

“The company has maintained its low-cost pricing philosophy and customer focus while generating strong financial returns. In its core business, its virtuous cycle of increasing scale with product and shipping vendors leads to better selection and prices, which it passes along to consumers—resulting in better value that leads to greater share of wallet and customer loyalty. In addition, Amazon.com’s financial model allows it to invest in new products and services such as the Kindle, permitting greater gains in market share while its competitors are cutting costs or services.

The fund beat the S&P in 15 out of 18 quarters but also experienced a fierce 46% drawdown during the financial crisis. "Some people would say it was better relative to its peers,” Ellenbogen told the Wall Street Journal, “but I was still not proud of that performance.”

Laporte’s lesson

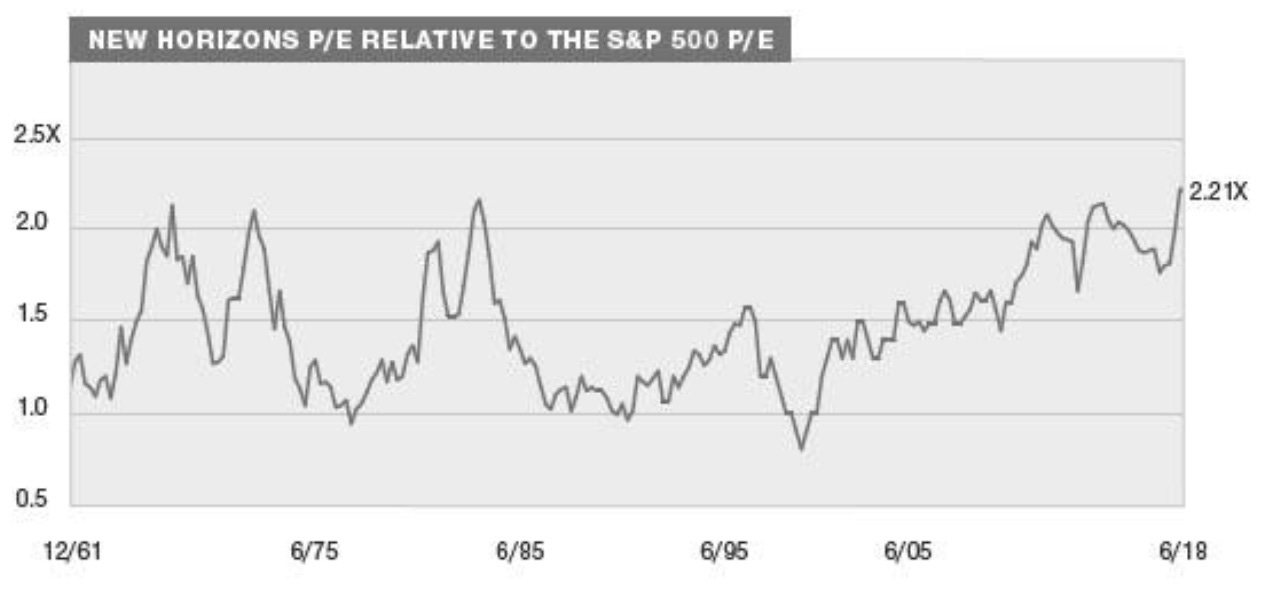

Ellenbogen joined the New Horizons Fund which dated back to 1961, another decade when growth stocks were very popular. The fund’s long history also provides us with these unique long-term valuation charts:

The fund had been run by Jack Laporte for 23 years. Ellenbogen called Laporte “instrumental” to his joining T. Rowe and thanked him for his mentorship. "If our industry had a hall of fame,” Ellenbogen wrote about Laporte, “he would be in it, but even that would understate his impact.”

Over the decades, Laporte and his predecessors had invested in “emerging growth” companies ("small-cap companies that have the potential to be much larger over time") such as Xerox, Texas Instruments, Wal-Mart, Starbucks, Paychex, and Medco Health.

“Investment ideas frequently arise from change within an industry or individual company, so ‘change’ in some form is an important factor in most of our investment decisions” Jack Laporte

On at least two occasions Laporte described his biggest investment mistake as selling a winner too early. He bought Starbucks at the IPO but sold the stock a few years later out of concern over rising coffee prices. At the time of his retirement, he also reflected on selling Walmart too early.

It seems he may have been able to pass along this valuable lesson to Ellenbogen.

Ellenbogen’s Playbook:

Eliminate the false dichotomy

“Our overall goal is to own companies that are innovative early-stage or durable growers with the potential to become much larger, successful firms over time as a result of their innovative business models. These stocks have the potential to generate solid long-term returns for our shareholders.”

Ellenbogen focused on identifying promising companies, “capable of bringing to market new products or business model innovations... benefiting from changing markets, or put another way, durable growth companies that are capable of compounding wealth over time by becoming leaders in their respective industries.”

He invested his fund roughly one third into early-stage growth companies (“rapidly expanding firms that have the potential to disrupt an industry and build a lasting franchise”) and two thirds into "durable growth companies,” better known as “compounders,” (which “leverage valuable competitive moats to gain market share and compound capital methodically over time”). This was a change from his early time running New Horizons when he described it as three buckets: “potential long-term winners, durable niche growth companies, and out-of-favor durable brand companies.”

“Although researching early-stage innovators takes up approximately half of our time, durable growth companies account for about two-thirds of the fund. In these businesses, we seek superior business and financial models coupled with management teams that effectively execute on a daily basis while also positioning their companies for future success. In addition, we look for companies with a high and growing return on invested capital.”

“We spend significant effort examining the entire ecosystem of industries that can produce value over time. We seek out entrepreneurs, venture capitalists, and innovators to learn about the trends in their industries and search for unique companies that can define their markets. We look for companies that possess an ethos of innovation, strong management teams, and solid underlying business models.”

If Ellenbogen was looking to invest in the best growth companies, he had to study venture stage companies. The synergies of investing in both public and private markets became obvious. He therefore started the fund’s private investing program, which grew to account for 5% of the portfolio.

“We view our private investing as an extension of our early-stage growth investing discipline and not as a distinct practice.”

In his 2020 podcast interview he rejected the idea of siloing his team between private and public markets. He called this the false dichotomy of the "endowment model" and the "Morningstar box". Instead, he believes there are significant synergies of having a collaborative team with a holistic understanding of interesting sectors in both public and private markets.

"It sounds so simple, but it’s very hard to operate. … At Durable, we don’t have private investors and we don’t have public investors. We don’t have early-stage growth investors and we don’t have durable-growth investors. And we don’t have people who work on deals. We have world-class security analysts who know early-stage growth and durable-growth and who want to be part of compounding … We eliminate these false dichotomies that I believe have been forced upon our industry by, I would oversimplify it, the Endowment Model and the Morningstar Box Model.

We want to be involved in small companies that one day become large, are in balance with their environments, and are being run by people who have an ownership mindset, and we eliminate these false dichotomies."

Real winners are rare

Ellenbogen is acutely aware that long-term compounders are rare and account for a large share of the market’s performance (see also Henrik Bessembinder’s studies for more info on the distribution of returns).

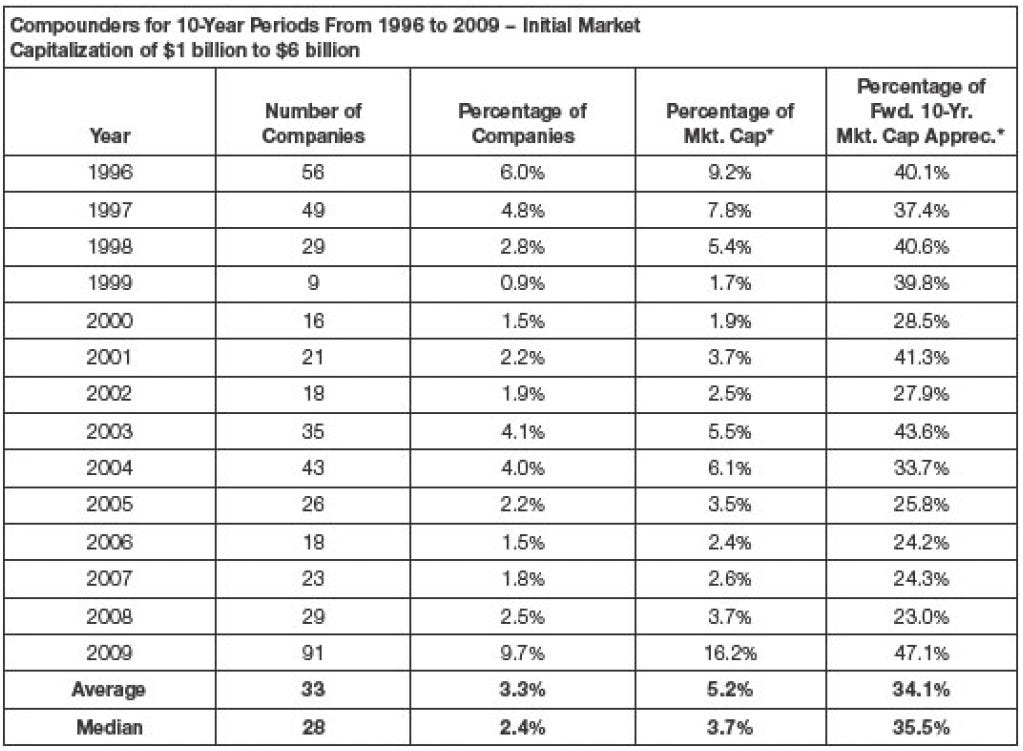

“We began to study an elite group of these compounders, across the universe of small-cap, publicly traded companies since 1996. We found that small-cap compounders—U.S.-listed companies that began with $1 billion to $6 billion market capitalization and subsequently generated a 20% total return compound annual growth rate (CAGR) over a 10-yearperiod—are rare and extremely valuable to returns over time.

Since 1996, there have been 463 instances where small-cap companies passed the 10-year return hurdle to be designated as a compounder. The median number of small-cap compounders was 28 per year, or 2.4% of eligible companies during the 10-year period.”

“An annual cohort of small-cap compounders contributed nearly 35% of the total market appreciation over the 10-year period. Said differently, compounders were nearly 15 times more impactful to the market’s returns than the number of companies would imply on its own.

This data reaffirmed our views that small-cap compounders are rare—historically 1 in 40 companies achieved the feat—and the stakes are very high for investors. This reminds us that, as growth investors, we need to grow our roses and cut our weeds.”

His goal is to participate in the compounding for as long as possible. He can invest in a company while private and average up through subsequent funding rounds or by adding to the position after the company goes public. This is part of his pitch to founders as well:

“We do not invest in private companies merely to guide them to an initial public offering or benefit from private-public arbitrage. Rather, we want to serve as a stable partner that encourages businesses to compound wealth in the long run through durability and sustainability.”

He is comfortable averaging up if the company performs well and turns out to be one of his rare compounders.

“Our goal is to buy shares in our successful early-stage growth companies as their stock price is rising, but in our view, has not yet peaked. We call this “dollar cost averaging up.””

“When we invest in a private company, we tell the chief executives that we seek to deploy capital in companies that can become long-term holdings. Our goal is to compound wealth in these companies as they scale and transition from early-stage to durable growth companies, and we often increase our stake as they scale.”

Looking for second acts

At the core of Ellenbogen’s framework is the idea that the most successful growth companies have multiple acts. After exhausting their initial growth potential, they must transition to a second act – new markets or products. Ellenbogen admits the futility of trying to predict how this will unfold. Instead, he focuses on identifying the driver that is a necessary condition: exceptional leadership willing to invest long-term and build out processes that will support a larger scale company.

“We seek companies that have the potential for an Act 2. These enterprises have the ability to find a second phase of growth—a new product, additional market, or innovation—after their first growth engine, or Act 1, has run its course. Act 1 companies that successfully transition to Act 2 have been critical to our outperformance, and we aim to partner with them as early as possible.

When we look at an early Act 1 business, we want to know that it is building the people, processes, and systems necessary to keep winning at scale. We care about management’s willingness to invest for the future, not just its ability to execute in the present.

Transitioning to Act 2 requires a number of skills, including the ability to properly balance customers, employees, and shareholders; to construct a strong corporate culture; and to foster an ownership mentality. But most importantly, managers need the ability to adapt and transition.

Inevitably, the Act 1 to Act 2 transition will result in a challenging period, and transitions are difficult. Vital to doing this successfully is a commitment to intellectual honesty, diversity of thought, and emphasis on organizational adaptability.”

This is part of his conversation with private companies as well:

“One of the principal reasons we invest in private companies is to encourage them to think about scale in people, processes, or systems. Often, our best contribution is introducing companies to outside executives who understand the concept of scale.”

“During the initial growth period, management teams focus on investing in their products to achieve product-market fit, building solid initial leadership teams, and solidifying unit economics that work at scale. Most investors spend time thinking about the size of the company’s addressable market and its potential to demonstrate a competitive edge in Act I alone.

Even at the beginning stages of a company’s expansion, we look beyond Act I and understand whether the business has the potential for a second act.”

Example: Vail Resorts

“When we first bought the stock in 2010, Vail was considered a real estate company. But we saw a company in transition, moving from a transactional toward a subscription business with high returns on capital and a network effect, underpinned by world-class data and data-based marketing. Today, Vail has 645,000 customers who subscribe before Thanksgiving to ski.”

“We initiated our position in Vail Resorts between 2010 and 2012 believing that Vail offered a unique investment opportunity that could benefit from a cyclical recovery in skier visits. The company had introduced an attractive season pass program that was allowing it to gain local and regional market share.

By 2014, the stock had nearly doubled, and we opted to sell about 10% of our position, following an unexpectedly strong earnings report and an announcement that Vail would acquire Park City Mountain Resort. It is easy to be critical of those stock sales with the benefit of hindsight. First, the 2014 fiscal year results showed that season pass sales had stabilized Vail’s financial performance despite a historically weak ski season in Tahoe, where Vail has two ski resorts. Second, the acquisition of Park City expanded Vail’s ski network, which made the season pass even more attractive to customers.

Over the following year, we did further due diligence. Our work showed that when Vail reported its results for 2015—the first year Park City was included in the network—season pass sales growth accelerated. Furthermore, the company gained more scale against its fixed costs to improve margins, increase the customer experience, and improve return on invested capital for shareholders. Following this bottom-up analysis, the fund increased its position in Vail by about 15% at an average cost of $125, or more than triple our historical average purchase price, and separately acquired about a 10% ownership stake in Whistler Blackcomb. We believed that Vail could pay a substantial premium to Whistler’s prevailing share price and still generate an attractive return for shareholders.

Vail acquired Whistler Blackcomb in 2016 for cash and stock, which further increased our ownership stake in Vail by about 17%. Fortunately, we didn’t miss the opportunity to create value through dollar cost averaging up with this stock. We learned two valuable lessons from the Vail acquisition. First, we need to anticipate events and potential outcomes. Second, we should recognize that changes and improvements can be nonlinear, especially when buying into a network.”

It’s a people business: importance of leadership

"From the start, we always placed a premium on the chief executive and management team of private enterprises. In early-stage companies, leadership has an exponential impact on business success."

Venture capital is a highly competitive game for access to the best companies. Ellenbogen didn’t start out with a private investing track record or reputation and had to convince founders to partner with him over more established firms. In addition to his flexible, long-term capital he pitched his willingness to stand by his founders. “If you do what you say you're gonna do,” Ellenbogen said, “we're gonna be your long-term partner in both good times and bad." Deep relationships, he believes, are formed in tough times.

"How do we get access to these companies? It's because of the consistency of how we handle ourselves in tough times. It's great to tell you that we led private rounds in Twitter, Workday, Twilio, Atlassian, Datadog. It's easy to talk about your success. If it goes sideways, we have made a commitment to that entrepreneur to stand by them in tough times. I have made about 80 private investments. About half of the time in the first year they miss their numbers. "

"How do you act, what is your demeanor, what are your incentives and what is your alignment on people's toughest days?"

"I tell entrepreneurs, a lot of people want to invest in you on your best days. Who is going to be your partner on your worst day? Don't take my word for it, call Max Levchin. How did we stand by him with Slide, which had very tough times before it sold to Google. What was Max's experience with us. Or very recently you could pick up the phone and call the Warby Parker guys and ask them, how did Durable stand behind them when they had to close all their stores because of COVID and they wanted more capital."

He used the story of Pixar’s Toy Story 2, a movie that nearly failed, as an example of the "unusual intellectual honesty" required for leaders to navigate challenges. Ed Catmull called it “the most grueling production schedule we would ever undertake—the crucible in which Pixar’s true identity was forged.” The movie was fixed by the “Braintrust,” a group of problem-solvers who could analyze “without any of its members themselves getting emotional or defensive.” Ellenbogen looks for the same qualities in the leaders of his portfolio companies – and in his own team.

“For each early-stage company in which we invest, the goal is to watch a small company become a large company and compound wealth over a long period of time. The early-stage growth companies that we invest in share common traits: They have achieved an early product-market fit with initial market leadership, have a solid initial management team, and should achieve solid economics at a reasonable scale. Frankly, these traits are not much different than those that many of our competitors prioritize.

What makes our process different? We are looking for companies that can successfully have a second act (additional markets and products) and compete against the next set of peers. The common thread among these early-stage growth companies is the CEO and key leaders: Do they have the ability to scale people, processes, and systems? Can they create a culture that can adapt and learn? Are they intellectually honest about their challenges? When we make an investment, we cannot affirmatively answer these questions. However, we can very often answer the question: Are they the type of leadership that could have an act two?"

“When I was managing the T. Rowe Price Media & Telecommunications Fund, we started a monthly investment review process in which one analyst presented his or her thesis to two other analysts as well as the rest of the investment committee. The immediate goal was to further vet the investment thesis and determine the next appropriate step. The larger goal was to bring other perspectives to bear on the problem, looking for deeper insights that stem from examining one industry from the viewpoint of people with expertise in another.”

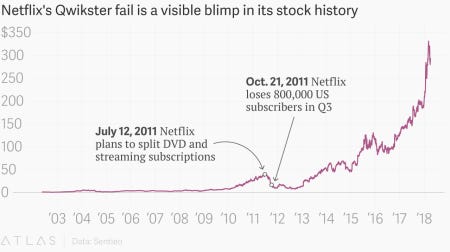

Example: Netflix

Netflix is another example of both a second act and the importance of leadership. Ellenbogen and T. Rowe Price supported the company with capital during its difficult transition.

“During the transition from its Act I as a delivery business to an Act II as a video streaming service, Netflix made several strategic missteps. It charged too much for a limited selection and announced a splitting of the company only to immediately retract it. This triggered a spike in customer churn rates, putting the company’s balance sheet at risk as it was making significant investments in building out its streaming business.”

“We invested in Netflix in the fall of 2011 when the market grew concerned about Netflix’s underlying financial model and the company’s ability to fund its content obligations following a series of management missteps. Our investment thesis on Netflix posited that the company had two ways to win: First, as demonstrated by the history of analog subscription services such as HBO and Showtime, possessing the scale to invest more than the competition in third-party content, original programming, and technology is vital to long-term success in the video content market. Based on Netflix’s large subscriber base and other scale advantages, we believed the company was in a strong relative competitive position.

Second, we were impressed with the collective work of the Netflix management team and the intellectual honesty they showed about their mistakes. Like others, we were concerned about the company’s customer churn, balance sheet, and lack of current profitability; however, we felt that Netflix had time to address these issues and other strategic options. We managed these risks through our position size.”

“We alongside TCV recapitalized Netflix after the whole Qwikster thing. T. Rowe put $250 million directly on the balance sheet. This is pre-split, the stock had gone from $270 to the low $70s. And there were a lot of issues at the time. Reid was being criticized on Saturday Night Live and there were a lot of upset people and the churn had spiked. But the one thing that you knew about Reid, as someone who had known him for ten years at that time, is that the guy was intellectually honest. He realized his mistakes and he went from buying back stock at $270 a share to realizing he had to sell stock to shore up his balance sheet at $70. I don’t know many portfolio managers who can go from buying something at $270 to selling it at $70 that quickly. That takes the ability to re-apprise the situation and be intellectually honest. For a founder and someone so close takes another level of skill. That’s a long way of saying that you really have to underwrite the people and how they’re going to perform on the field.”

Data-driven investing: KPIs, cohorts, alpha attribution

“Management teams need to be honest about their challenges. We like leaders who are data-driven and have a rational system of managing according to key performance indicators (KPIs), not according to unchecked intuitions. We find that most great companies view their customers as stakeholders and seek to build a product that will serve them, not just extract value from them.”

Like his favorite entrepreneurs, Ellenbogen is data-driven and likes to use KPIs to assess his portfolio companies and his performance.

“When we invest in a private company, we ask management to create one-page monthly KPIs [key performance indicators] separate from their board decks [information packets for board meetings]. CEOs quickly find that the discipline of having to put together a monthly one-page dashboard of how the business is doing creates an internal understanding of which metrics matter.

“One characteristic that we have observed in our best early-stage and durable-growth companies is a clear understanding of their business drivers, the desire to measure these drivers, and the ability to address underlying root-cause issues by adapting either strategically or operationally to navigate challenges. We have worked closely with many companies to sharpen the measurement of their KPIs—as we believe this helps to improve execution and aligns the conversations with key constituents.”

We get the benefit of a bit of a “data dump” in the 2018 letters. I suspect this was at least in part motivated by the desire to demonstrate Ellenbogen’s track record ahead of raising capital for his new firm.

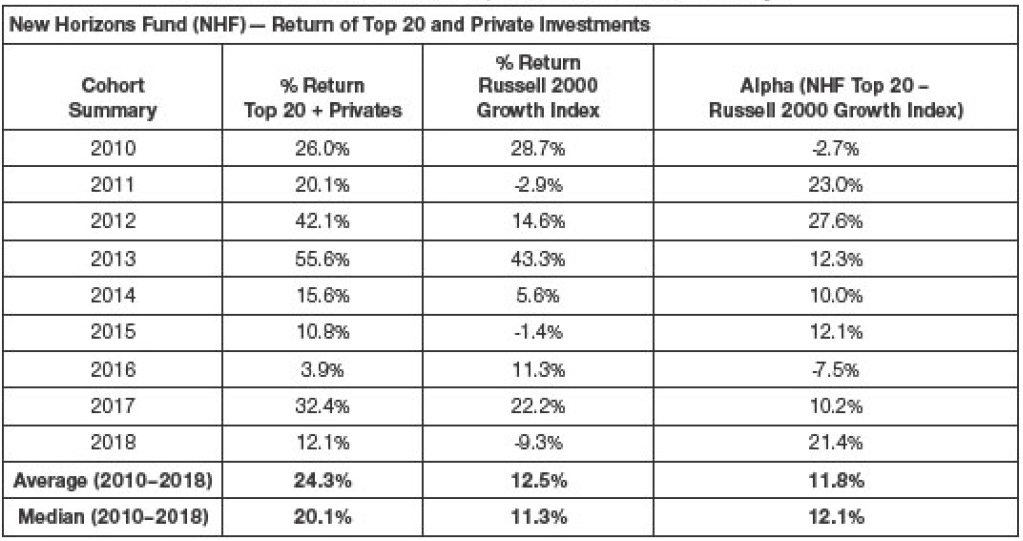

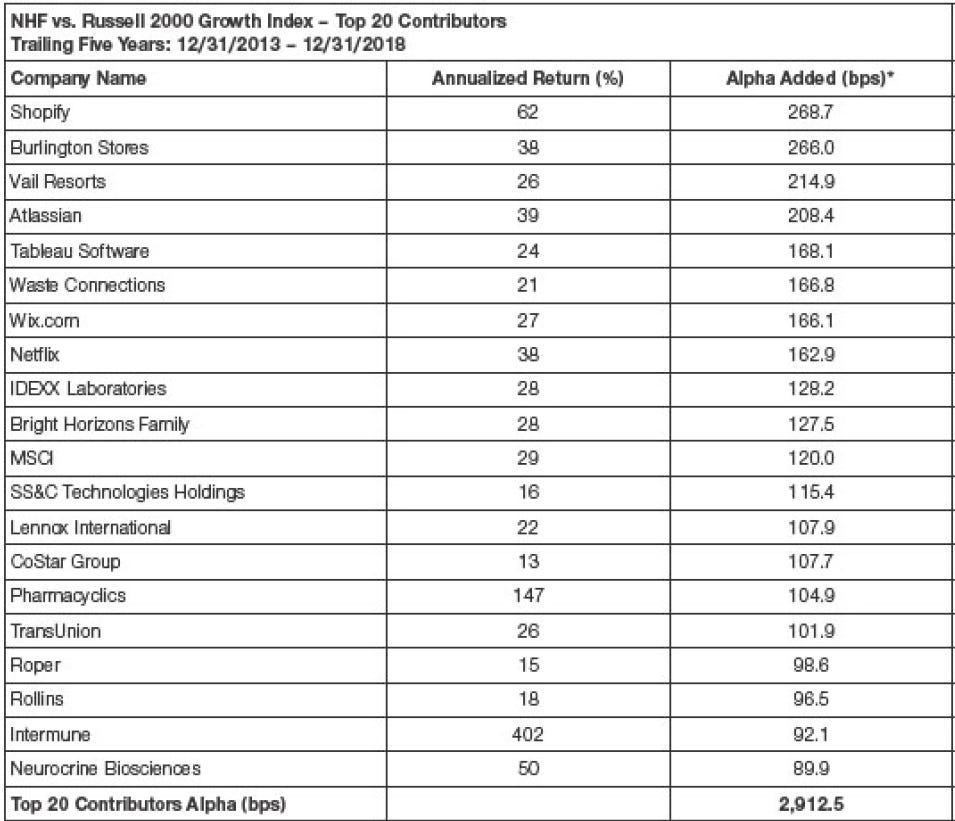

To assess his performance, he uses a vintage analysis (internally called a “Freshness Index”) of the top 20 public companies holdings and the top 20 public companies holdings as well as the private investments (data from the 2018 annual report).

“Our top 20 holdings are the companies for which we have the highest conviction and should have the largest impact on fund performance. With each of these holdings, we maintain individual company KPIs, meet with each management team, and encourage the executives to focus on building a durable and sustainable company—even if it results in lower short-term economics.”

“We track this methodology, like a sports team evaluating its draft classes, with what we call a “vintage analysis.” This analysis chronicles the performance and position size of all the holdings added to the fund in a particular year. As inflection points come to pass, we adjust position sizes as necessary; as a result, vintages tend to generate the greatest performance not in their first year, but in later years as they become more concentrated around companies with probable second acts.”

Top 20 holdings and private investments:

These were the top 20 contributors as of December 2018 over the preceding five-year period, not overly concentrated in technology and no FANG names other than Netflix since the New Horizon Fund’s mandate was to invest in smaller companies:

He also assessed his investments by holding period. The divergence in returns between short and long-term holdings is remarkable. Ellenbogen relentlessly cut his losers and let his winners run.

“First, we prune our holdings over time as we observe our companies develop and, as a result, we expect to own significantly fewer companies over the longer term. Second, as companies transition from early-stage growth to an Act II or prove themselves to be a durable growth company, we let compounding work in our favor by purchasing more stock at higher prices. Thus, we anticipate that our outperformance will be concentrated in holdings that we believe are worth owning for many years.”

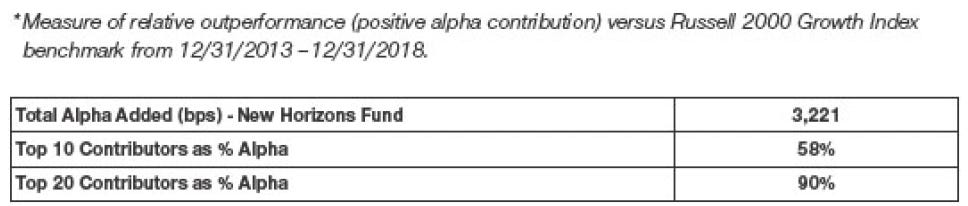

To assess his private investments, he did another cohort analysis (with a separate table for follow-on investments which you can find in the 2018 report if you’re curious). He waits for three years before evaluating performance and demands a significant return premium over the public benchmark. Looks like the program succeeded with flying colors.

“Our returns relative to the Russell 2000 Growth Index, the fund’s primary benchmark. We hope to outperform this benchmark by at least 1,000 basis points to provide a margin of safety given the illiquidity and higher risk of private companies.”

“We believe that it takes an investment cohort at least three years to mature before there are adequate data to measure success—thus we would focus on 2014 and prior cohort years.”

“The returns are sorted by cohort year, which includes all follow-on activity as occurring in the same cohort year as the initial investment, rather than splitting them based on calendar years.”

Private investments by cohort year:

He also provided a table of what he termed “private compounders,” investments whose value had increased to at least 6.2x the initial investment (equivalent of a 20% CAGR over a 10-year period, albeit achieved over a much shorter time period). Thus we get a breakdown of his most successful venture investments:

“Deeply human” investing

“You have to think about this practice [of investing] the same way you think about a business.”

In the 2020 podcast interview, Ellenbogen and his partner at Durable, Anouk Dey, discussed competing against quantitative investors:

“The framework we apply is one that applies to a lot of industries we study. The investment industry is bifurcating between robots and what we call 'deeply human investing.'” Anouk Dey

Ellenbogen added:

“If you're a fundamental investor you have to understand what the skillset of a human is and what the skillset of a machine is, and you have to continue to become greater at where humans are relatively advantaged. If we were to go play a game against the computer in chess, we already know who's going to win. That's like competing against the quant in a linear pattern that's been public for a long time against known alternative datasets.

If we could change the rules of the game right before we play, and the computer didn't know the rules and we knew the rules, I think we would win the game.

Patterns that are newly public, that are geometric. A people are geometric, they impact organizations because they hire As and capital allocate in an ‘A way,’ that's geometric. That's where we believe we're advantaged.”

This fits perfectly with playing in private markets where success is determined by access, relationships, and more qualitative analysis.

It also matches Ellenbogen’s statements about small-cap growth investing being both creative and complex:

“Dispersion in small-cap growth stocks, the rewards of success are greater and the penalties for failure are more severe. The broader interpretation is that developing and maintaining a creative process that encourages unconventional or controversial views of business models is essential to success in small-cap growth investing.”

“Growth investing is undeniably a complex problem. The concept of complexity applies particularly well to industries undergoing structural change. Our work demands that we interpret a constant stream of new, often-surprising data points and place them in an appropriate context. As a result, when we are measuring the probability of different outcomes, we have to rely heavily on our qualitative understanding of business strategies and industry trends.”

Conclusion

Similar to Nick Sleep, I like that Ellenbogen’s playbook boils down to a handful of “simple ideas, taken seriously”: Identify the elements of durable growth and leadership capable of second acts, build lasting relationships, create a fund structure that affords flexibility, reject the public/private dichotomy, strive for intellectual honesty, diversity of thought, and adaptability. These are simple but not easy to implement. But they create a unique process, culture, and a differentiated asset management business.

I like to think of Ellenbogen as someone who successfully modernized an investment mandate with a long tradition. He combined a “deeply human” investment approach with a data-driven process and a long-term perspective. I’m not surprised that he keeps compounding.

“It's about alignment. The best companies we've invested in do everything well. They don't do one thing well and the whole organization, from top to bottom, is aligned against the goal and they can clearly articulate the goal.”

“Our binding constraint for our team is time allocation as we seek to deliver world-class performance for our shareholders.”

The Durable Capital philosophy:

We look for the following characteristics from companies:

They are in balance with their environments

They have accountable management teams who view themselves as long-term owner-operators

They value intellectual honesty and humility

They emphasize long-term financial stability and durable advantage over financial gain resulting from unsustainable short-term growth

New Horizons Fund filings

2020 Value Investing with Legends podcast

Barron’s 2017, “A Noted Fund’s Bet On The Future Pays Off Today.” 2012 “Pick Wisely, And Wait.” Also a member of the Barron’s Roundtable.

Financial Times, 2014, “Technology bets propel small-cap winner”

If you enjoyed this piece, could you please do me a favor that costs you nothing? Please consider simply clicking the “like” button when you are done reading. New readers look at the number of likes as an indicator of whether to subscribe and spend more time reading a Substack. I know it’s a silly metric but I think it would encourage more people to read and become subscribers. It’s up to you. But pressing the heart at the end of a piece costs you nothing and would make my day. Thank you all for reading.❤

Thoughtful piece. Made me think about how i think about companies and how i invest.