📚Investment Library: The Money Game

“Enjoy the stories, they always teach more than the rules.” George Goodman, The Money Game

Published in 1968, The Money Game by George Goodman (under the pseudonym ‘Adam Smith’) is one of my favorite books about the psychology and antics of professional investors.

Goodman was writing at a time when a new generation of aggressive, growth-oriented investors was emerging and rebelling against the pervasive conservatism instilled by the memory of the Great Depression.

“The strongest emotions in the marketplace are greed and fear. In rising markets, you can almost feel the greed tide begin. Usually it takes from six months to a year after the last market bottom even to get started. The greed itch begins when you see stocks move that you don’t own. Then friends of yours have a stock that has doubled; or, if you have one that has doubled, they have one that has tripled.”

The 60s go-go bull market shared many similarities with the past few years, including a boom and nosebleed valuations in technology stocks and wild speculation in small (also: enterprising value investors built conglomerates).

As the editor of the new Institutional Investor magazine, Goodman immersed himself in the world of investors and speculators. He shared their gossip and attended their idea lunches. By becoming a trusted insider he was able to capture their mindset, quirks, and motivations.

“A fund manager will tell another fund manager the innermost state of his emotions, the condition of his marriage, and even his purchases and sales, but he will not tell a broker or a magazine or any outsider who is likely not to understand him completely.”

The Game

Both in his witty prose and his message, Goodman was part of the rebellion against Wall Street’s stuffiness and rigidity. “We are taught,” he wrote, “that money is A Very Serious Business, that the stewardship of capital is holy, and that the handler of money must conduct himself as a Prudent Man.” That was not what Goodman observed in the market. He saw the excitement, the anxiety, the passion. He found his favorite metaphor in the writing of his idol, John Maynard Keynes:

“The game of professional investment is intolerably boring and over-exacting to anyone who is entirely exempt from the gambling instinct; whilst he who has it must pay to this propensity the appropriate toll.”

“Game? Why did the Master say Game?” Goodman mused.

“He could have said business or profession or occupation or what have you.

What is a Game? It is “sport, play, frolic, or fun”; “a scheme or art employed in the pursuit of an object or purpose”; “a contest, conducted according to set rules, for amusement or recreation or winning a stake.”

Does that sound like Owning a Share of American Industry? Participating in the Long-Term Growth of the American Economy? No, but it sounds like the stock market.”

Goodman was on a mission to rediscover the human side of the market among the emphasis on data and charts. He was fascinated by the players who seemed so passionate, compulsive even, in their pursuit of success. Even the professionals oscillated between rational analysis, intuition, and emotion.

All of this, Goodman thought, was not reflected in the writing about the market. Research and commentary emphasized facts and rational decisions. Meanwhile, investors were led astray as they wrestled with their own psychology and biases.

“It has taken me years to unlearn everything I was taught, and I probably haven’t succeeded yet. I cite this only because most of what has been written about the market tells you the way it ought to be, and the successful investors I know do not hold to the way it ought to be, they simply go with what is.”

The most important parts of the book deal with that departure from rationality. Today, we have a much better understanding of this but Goodman was writing before the advent of behavioral economics. He explored it by closely observing investors at work and collecting their stories. “There is one requirement that is absolute in money managing,” Goodman wrote. “The requirement is emotional maturity.”

“A series of market decisions does add up, believe it or not, to a kind of personality portrait. It is, in one small way, a method of finding out who you are, but it can be very expensive. This is the first Irregular Rule: If you don’t know who you are, this is an expensive place to find out.”

The real object is playing

Some of the book’s most quotable paragraphs describe the players’ obsessive nature, their borderline addiction. Goodman viewed this as a prerequisite to be competitive.

“If you are a successful Game player, it can be a fascinating, consuming, totally absorbing experience, in fact it has to be. If it is not totally absorbing, you are not likely to be among the most successful, because you are competing with those who do find it so absorbing.”

The litmus test was whether a player was in the game merely for money or for the experience of playing and competing. The real players, Goodman argued, could not find peace in retirement.

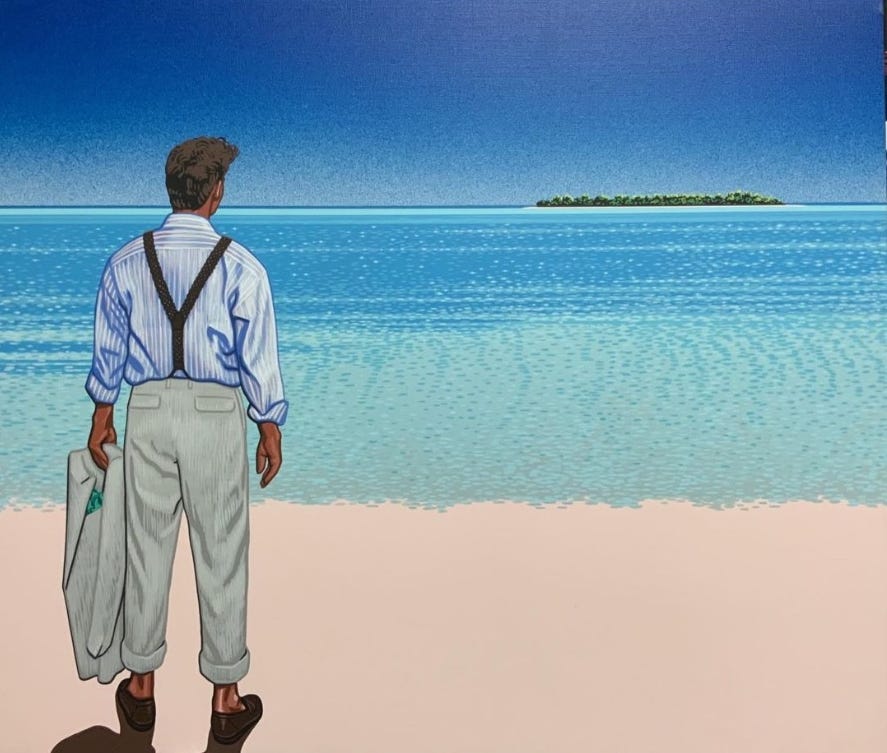

“I have known a lot of investors who came to the market to make money, and they told themselves that what they wanted was the money: security, a trip around the world, a new sloop, a country estate, an art collection, a Caribbean house for cold winters.

And they succeeded. So they sat on the dock of the Caribbean home, chatting with their art dealers and gazing fondly at the new sloop, and after a while it was a bit flat. Something was missing.”

They were drawn back to the game, to the puzzle, the mystery, the fun, and the opportunity to prove themselves. Competing against the market was a deep need they could not let go off.

“The irony is that this is a money game and money is the way we keep score. But the real object of the Game is not money, it is the playing of the Game itself. For the true players, you could take all the trophies away and substitute plastic beads or whale’s teeth; as long as there is a way to keep score, they will play.”

Goodman recognized how dangerous this compulsion could be. A core theme of the book is that the game puts the devoted player in a perpetual state of anxiety. But to play successfully requires patience, discipline, and peace of mind — serenity in the face of tension.

Goodman was writing during a bull market, well aware that the good times would eventually come to an end.

“One day the orchestra will stop playing and the wind will rattle through the broken window panes. We are all at a wonderful party, and by the rules of the game we know that at some point in time the Black Horsemen will burst through the great terrace doors to cut down the revelers; those who leave early may be saved, but the music and wines are so seductive that we do not want to leave, but we do ask, ‘What time is it? what time is it?’ Only none of the clocks have any hands.”

What he didn’t anticipate was that the heroes of the book, the fast-acting, intuitive gunslinger managers, would mostly go under. They got drunk on their own success and overstayed their welcome.

After writing the book, Goodman profiled Buffett (and Buffett later appeared on Goodman’s TV program) and Buffett recommended The Money Game in his annual letter as a “magnificent account of the current financial scene”.

“Get a copy of “The Money Game” by Adam Smith. It is loaded with insights and supreme wit.”

I couldn’t have put it any better.

Subscribers can continue reading for my favorite quotes and takeaways from the book.

The toughest thing is not to play

Goodman was a “consistent growth” investor. As growth stocks, and later the Nifty Fifty, took off, he reminded himself that no strategy could be expected to perform well in all markets.

“Value is not only inherent in the stock; to do you any good, it has to be value that is appreciated by others. It follows that some sort of sense of timing is necessary, and you either develop it or you don’t.”

“To everything there is a season … There isn’t anything else to say. There are some markets that want cyclical stocks; there are some that do a fugal counterpoint to interest rates; there are some that become as stricken for romance as the plain girl behind the counter at Woolworth’s; there are some that become obsessed with the future of technology; and there are some that don’t believe at all.”

There was no formula, no system, to consistently beat the market. But Goodman believed it would be nearly impossible for a dedicated player to step aside when their strategy was out of favor.

“Nothing works all the time and in all kinds of markets. This is what is wrong with systems and the books that tell you You Can Make a Million Dollars. What is important to realize is that the Game is seductive.

If playing it has been fun, it may be difficult to stop playing, even when that button of yours is burning your finger. Repeated shocks will give you anxiety, and anxiety is the enemy of identity, and without identity there is no serenity.”

Echoing Druckenmiller’s sabbatical, one of the book’s characters recognized the futility of going up against a hostile market. But instead of taking a break, he was drawn into a commodity speculation. The game was too seductive and the story ends with the incineration of the speculator’s capital.

“We should all go away for a year and come back fresh, just as everybody is fatigued from riding the market down and watching it rally,” said the Great Winfield. “But we can’t do nothing for a whole year, so I have us something that will give us ten times our money in six months.”

Even the pros, especially the pros, can’t help themselves. The game is too seductive.

“It is impossible to resist: international intrigue, the mockery of socialism, the chance to profit by the tides of history. “Tell me the game,” I said.

What do they want out of markets?

“Win or lose, everybody gets what they want out of the market,” legendary trader Ed Seykota once said. He was hinting at traders’ unconscious motivations, noting that “some seem to like to lose, so they win by losing money.”

There is an inner game to investing and trading. One part of it is to understand one’s motivation and avoid the trap that Seykota described.

“I think that if people look deeply enough into their trading patterns, they find that, on balance, including all their goals, they are really getting what they want, even though they may not understand it or want to admit it.” Ed Seykota

Goodman agreed and devoted a chapter to characters that happily engaged in markets despite a lack of success.

“If they make a little money, they’re happy, if they lose a little money, they’re not too unhappy. What they want to do is to call you up. They want to say, ‘How’s my stock? Is it up? Is it down? What about the earnings? What about the merger? What’s going on?’ And they want to do this every day, they want a friend, they want someone on the telephone, they want to be a part of what’s going on.

If you gave them a choice between making money, guaranteed, or staying in the game, and if you put it in some acceptable face-saving form, every last one of them would pick staying in the game. It doesn’t make sense, or the kind of sense you expect, but it makes a nutty kind of sense if you see it for the way it is.”

Beneath the search for profit lurked desires for fun and excitement, for community, friendship, and acceptance, for affirmation of identity, both good and bad.

I recommend Rob Henderson’s piece The Games People Play for a framework of the games people play in search of emotional payoffs.

“Payoffs: The benefits of the game; how it contributes to internal mental stability; how it avoids anxiety-arousing situations; the kind of strokes the game offers to those involved; and the existential point of view the game vindicates (perhaps the most important aspect of the game).”

Self awareness

This leads us back to the importance of self knowledge: “if you don’t know who you are, this is an expensive place to find out.” This is about more than understanding the factors impacting one’s decision-making.

“If you are not automatically applying a mechanical formula, then you are operating in this area of intuition, and if you are going to operate with intuition—or judgment—then it follows that the first thing you have to know is yourself. You are—face it—a bunch of emotions, prejudices, and twitches, and this is all very well as long as you know it.”

It’s about more than understanding when one is out of step with the market.

“Successful speculators do not necessarily have a complete portrait of themselves, warts and all, in their own minds, but they do have the ability to stop abruptly when their own intuition and what is happening Out There arc suddenly out of kilter. A couple of mistakes crop up, and they say, simply, “This is not my kind of market,” or “I don’t know what the hell’s going on, do you?”

It is about an awareness of one’s motivations, anxieties, desires, even trauma. A lack of understanding can leave the investor stuck, repeating an endless loop of behaviors that lead to mistakes.

You are not your score

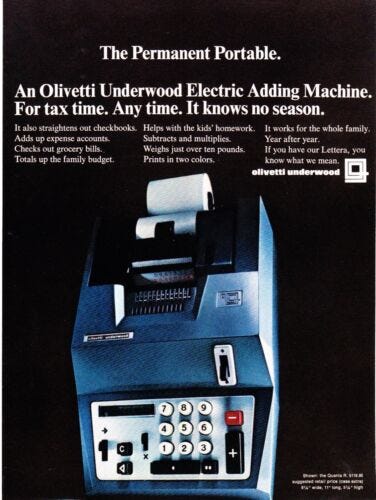

This is especially dangerous because players of the money game tend to attach their identity and sense of self worth to their net worth (“this is a money game and money is the way we keep score”). Because invariably, the investor will live through a downturn.

“Usually we hear only the triumphs by adding machine, but those who live by numbers can also perish by them, and it is a terrible thing to have an adding machine write an epitaph, either way. When the identity card says, “He had Sperry at 16,” or “He made 200 thou last year,” or “He is worth a mil easy,” then there are the seeds of a problem.

We all know what a millionaire is, and when the adding machine says, “$1,000,000,” there is a beaming figure facing it. But when the machine says 00.00 there should be no one at all because that identity has been extinguished, and the trouble is that sometimes when the adding-machine tape says 00.00 there is still a man there to read it.”

That last line absolutely haunted me. There is still someone to read it. And that person, painful as it may be, must find the compassion and courage to get up again and keep going. They are not their score.

Also, yes, Goodman operated in the age of ‘adding machines’...

Seeking serenity

“The end object of investment is serenity, and serenity can only be achieved by the avoidance of anxiety, and to avoid anxiety you have to know who you are and what you’re doing.”

Because Goodman saw investor psychology as the enemy of success, his answer was to do inner work. Find inner peace to navigate the anxious world of markets.

“If the occupation is money-making in its pure raw white form, then anxiety must always be present, almost by definition, because there is always a threat that the money which represents the achievement can melt away.”

Resolve any inner conflicts that could undermine your efforts:

“Your emotions must support the goal you’re after. You can’t have any conflict about what you’re after, and your emotional needs must be gratified by succeeding at what you’re doing. In short, you have to be able to handle any situation without losing your cool, or letting your emotions take over. You must operate without anxiety.”

This sounds like a mindfulness practice to me:

“The first thing you have to know is yourself. A man who knows himself can step outside himself and watch his own reactions like an observer.”

Develop an awareness of those motivations and recognize when they surface.

“Sometimes illusions are more comfortable than reality, but there is no reason to be discomfited by facing the gambling instinct that saves the stock market from being a bore. Once it is acknowledged, rather than buried, we can “pay to this propensity the appropriate toll” and proceed with reality.”

Adopt the gambler’s mindset of separating decision/process and outcome:

“But Harry was not really a gambler. You can tell those with the propensity: If the stocks are not moving they will play backgammon, and if not backgammon, they will be laying off on the football games, and if all else fails there is the gamble of which raindrop will make it first down the window. But they know themselves, and their identities are not in any one raindrop.”

And have an identity that is firm and separate from the score: “the identity of the investor and that of the investing action must be coldly separate.”

“The only real protection against all the vagaries of identity-playing, and against the final role of being part of the crowd when it stampedes, is to have an identity so firm it is not influenced by all the brouhaha in the marketplace.”

On analysts and portfolio managers

This is another great section in the book and worth reading carefully if you’re in the business. I’ll just share a few of my favorite quotes.

As I mentioned, Goodman romanticized the aggressive and intuitive portfolio managers that would mostly succumb during the bear market. Nevertheless, he surfaced some timeless ideas.

“Some analysts should not manage their own money, some portfolio managers should be running funds with other characteristics, and some investors should be cutting flowers in their garden and letting smart people run the money.”

“What is it the good managers have? It’s a kind of locked-in concentration, an intuition, a feel, nothing that can be schooled.”

“There is a personality difference between the people who are good at finding stocks and the people who call the shots on the timing and manage the whole portfolio.”

“The analyst is inductive. He will break the problem into its components and work away at each, building up to the answer. The old portfolio manager will settle happily into the problem; he loves it. The aggressive portfolio manager says, “What the hell kind of stupid question is that, and how is that going to make me any money?” and goes into the same kind of rage he did when his wife wouldn’t leave the party. He has to get the Concept in one fell swoop or he is very restless.”

“While the analysts can do the problems, they make a lot of arithmetic errors, unlike the accountants, who get everything right to the decimal point. But good analysts have high aptitude with both words and numbers. They shine best in vocabulary. It is when the functioning gets abstract, both numerically and verbally, that they begin to fade.”

“The analyst really wants to be right, his ego needs the pleasure of being right, and he would almost rather be right than make money. The aggressive portfolio manager doesn’t really care about being right on each judgment, as long as he wins when you tot up the score.”

Apperceptive mass

“Professional money managers often seem to make up their minds in a split second, but what pushes them over the line of decision is usually an incremental bit of information which, added to all the slumbering pieces of information filed in their minds, suddenly makes the picture whole.”

Buffett described this as the cumulative knowledge built up over decades of studying companies and industries. Soros had his back ache as a signal of his embodied intuition. After decades of immersion in markets they can make decisions in minutes.

Goodman used the example of the Rorschach test. What an investor sees in a given situation, whether they observe any pattern to act upon, tells us more about the investor and their experience than it does about the situation.

“The point of the blots is not what you see in the blots, but your response pattern to them. How high is your evidence demand? That is, how much do you have to see before you will commit yourself?”

For inexperienced investors, this kind of intuitive behavior can be dangerous.

“The small investor has the reaction without the knowledge. He has no “apperceptive mass” behind the reaction; the portfolio manager, quite simply, can remember the profit margins of a hundred companies, how the stocks react to a variety of situations, and where in the spectrum of managers he himself fits. If he knows these things, he can be away from the market and still know where its rhythm and his are meshing. In short, if you really know what’s going on, you don’t even have to know what’s going on to know what’s going on.”

Finding the smart people

Goodman called this one of the most important of his rules because “if you can [find smart people], you can forget a lot of the other rules.” He used Phil Fisher as an example who admitted to getting more ideas from his network than from scuttlebutt research.

“Phil Fisher is an honest man, and one day he sat down and made a study of where his successful ideas had come from. He found that only one sixth of the good ideas had come from the scuttlebutt network.

Fisher: “Across the nation I had gradually come to know and respect a small number of men whom I had do outstanding work of their own in selecting common stocks for growth.… since they were trained investment men, I could usually get rather quickly their opinion upon the key matters.… I always try to find the time to listen once to any investment man.”

Goodman: “Professional investment managers may, in the course of their careers, come to know by heart five hundred companies, what their histories have been, what their problems are, who makes up their managements, what their prospects are. But no one can cover everything, and no one can know everything. So most professionals depend on the people—their own analysts, other people’s analysts, other managers, their friends—whom they have come to respect as acute intelligences and as talents at whatever course—red, blue, or yellow—they happen to be talented at. There are really no more brilliant investment men than there are brilliant lawyers or top-flight surgeons.”

Well, there you have it. Read, make friends with smart people, and do the inner work. (Or just bet on the next Warren Buffett😉).

Until next time.