Stalking Bubbles: Paul Tudor Jones, 1987-1990

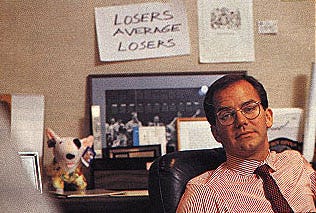

“Don’t be a hero. Don’t have an ego.”

A long-term stock chart makes history look deceptively simple. All context and emotion have been removed. The fog of war has been lifted. Of course, we say, the big bubbles that formed eventually imploded. And look at the crashes and minor bear markets, mere blips on the roads of long bull markets. Investing starts to look easy and straightforward. That’s why I like to dig into biographies and old articles. They allow me to step into the shoes of someone who had to navigate history as it unfolded.

But rarely can we follow an investor’s thinking over the course of an investment. More often that not we get an isolated soundbite. Maybe a brief write-up in a letter. We’re left to wonder: how did they weigh new information? Did they change their mind? The reluctance to comment publicly is understandable. For established managers there is more downside than upside. Making a public call opens you up to criticism and the risk of embarrassment. It can also attach your ego further to the idea, making it harder to change your mind.

Picture my excitement when I saw that Paul Tudor Jones had participated in the Barron’s Roundtable for several years after the 1987 crash. Every January he shared his views on markets and the economy. His comments, together with the Market Wizards book and a few articles, provided a unique view of his process and the evolution of two “big short” trades. Jones became famous after shorting the US market in 1987. What is less known is that he continued to stalk both the US and Japanese stock markets, expecting both to collapse, 1929-style.

It’s a case study in patience and pragmatism. Both markets rallied for years as Jones maintained a bearish macro view. Yet he didn’t blow up his fund or turn into a perma-bear over the market behaving opposite to his views. Jones carefully managed his risk, weighed the evidence, and eventually was able to short the bursting Japanese bubble while simultaneously changing his mind on the US market, which hadn’t been in a bubble after all.

Jones started his trading career in 1976 in cotton where a family connection allowed him to get into the business. By 1980 he set up his own firm, Tudor Investment Corporation with capital from friends and family as well as the famous trading house Commodities Corp.

After the miserable stagflation of the 1970’s, the 1980’s turned into a boom time on Wall Street. Interest rates had peaked declining, Reaganomics was boosting the economy with lower taxes and significant spending. Stock valuations were low and Milken’s junk bond machine provided the capital for large scale takeovers. Fortunes could suddenly be made in leveraged buyouts, activist raids, greenmail, and arbitrage.

This zeitgeist was captured by an exchange in the movie Wall Street between the “too much cheap money” Lou Mannheim (surely a follower of Graham and Fisher) and the impatient yuppie Bud Fox.

Bud: “Lou, I got a sure thing. Anacott Steel.”

Mannheim: “No such thing except death and taxes. No fundamentals, not a good company any more. What's going on, Bud? You know something? Remember there are no shortcuts, son. Quick buck artists come and go with every bull market, but the steady players make it through the bear market. You're a part of something here, Bud. The money you make for people creates science and research jobs. Don't sell that out.”

Bud: “You're right, Lou, you're right. But you gotta make it to the big time first, then you can be a pillar and do good things.”

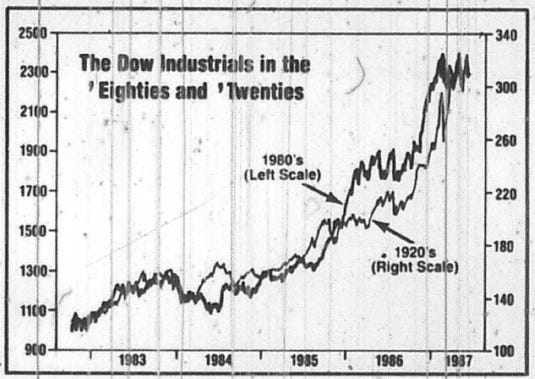

It’s not difficult to see why people started drawing parallels to the 1920’s: Wall Street was booming, debt was rising, the mood was optimistic and greedy:

“There is a common pattern in the 1980s and the 1920s of belief in `letting capitalism rip`, and reducing tax rates … There is also an obvious parallel in yuppie enthusiasm and speculation in investments, coming in a political climate that believes this is a productive and safe thing… Economically ambitious young people of The Great Gatsby era resembled today`s goal-oriented young people. Books on making money and capitalism were best-sellers. Old-line industries were suffering while financial and service industries were encouraged and booming.”

The Crash of 1987

“The week of the crash was one of the most exciting periods of my life.” Paul Tudor Jones1

In June 1987, Jones was profiled by Barron’s.

He discussed his bearish outlook on the US stock market based on two ideas, one more fundamental (albeit anecdotal), one technical. He noted an exuberance in markets like in fine art, a rapid rise in debt levels and bank leverage, stress in the oil patch and farm areas, low corporate liquidity.2

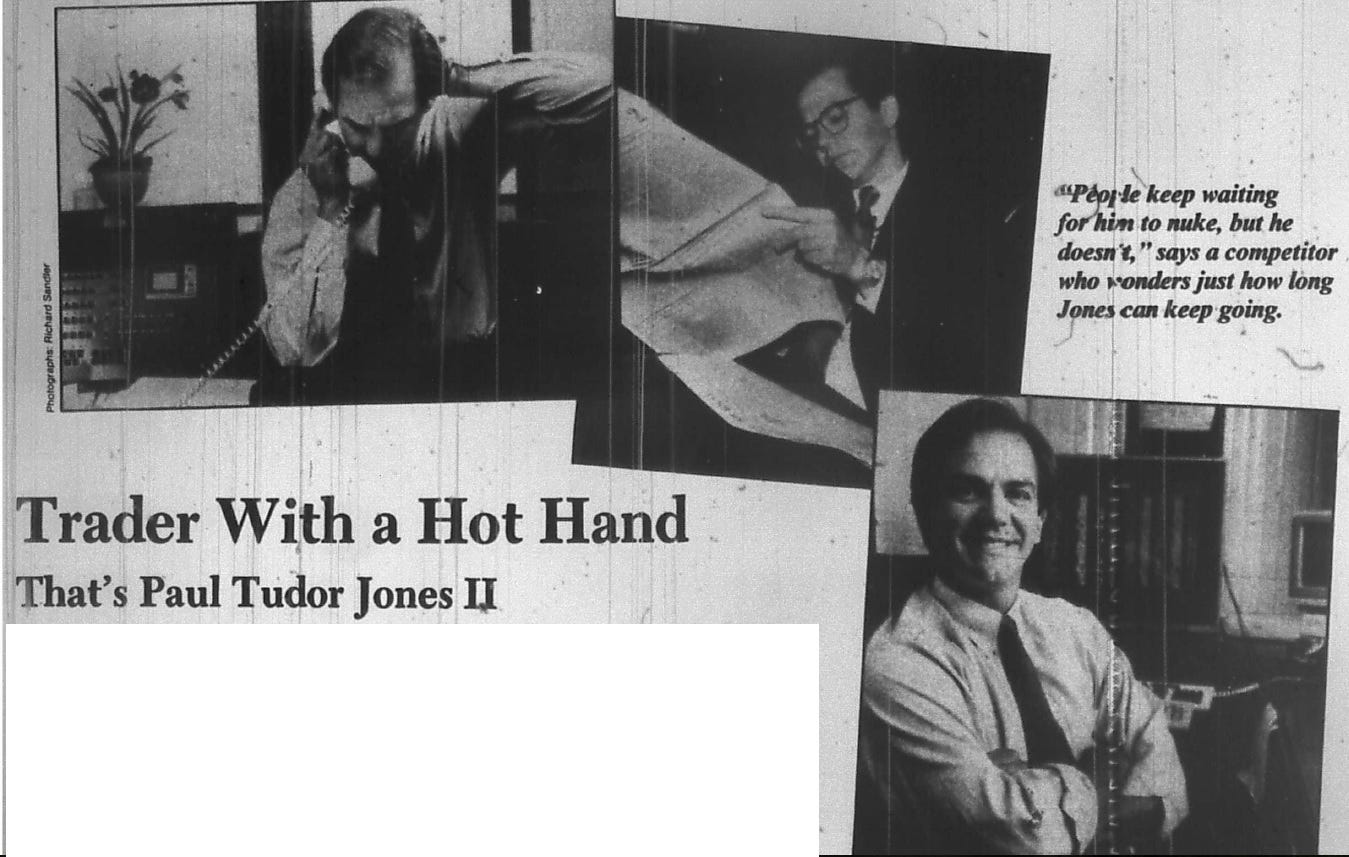

Jones also used an “analog model” (an overlay chart) that his research director Peter Borish had put together. The chart compared the stock markets of the 1920’s and the 1980’s and showed an “astonishingly robust” correlation. In addition, he noted how the Dow Jones Index had started to deviate from its long-term trend. Prior spikes had occurred in 1836, 1929, and 1966 - all followed by bear markets.

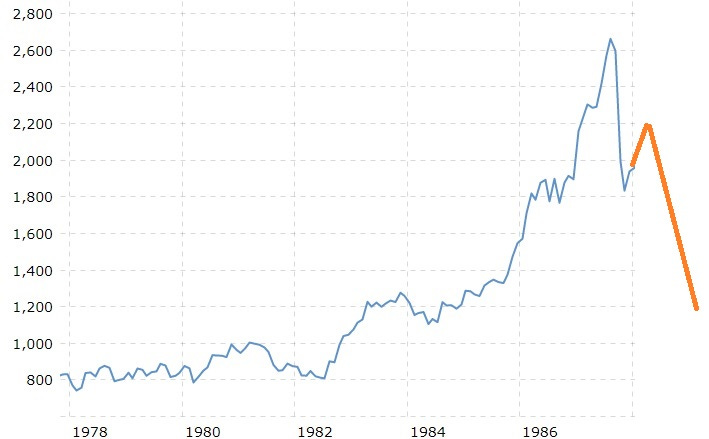

The infamous overlay chart:

(I apologize for the quality. I got this off a dusty microfilm in the basement of the New York Public Library.)

And the Dow Industrials “deviating from its trend” with spikes in 1836, 1929, 1966, and 1980s:

In the article Peter Borish actually admitted to “fudging the exercise somewhat by juggling the starting periods.” Nevertheless, Jones expected a 1929-style crash.

“I feel that you have to start getting short now because the panic, when it comes, will be so violent and sudden that the longs won’t be able to get out nor the shorts get aboard.”3

As a funny aside, on the Friday before the crash Stan Druckenmiller went to see George Soros who showed him Jones’s charts.

“That Friday afternoon after the close, I happened to speak to Soros. He said that he had a study done by Paul Tudor Jones that he wanted to show me. I went over to his office, and he pulled out this analysis that Paul had done about a month or two earlier. The study demonstrated the historical tendency for the stock market to accelerate on the downside whenever an upward-sloping parabolic curve had been broken-as had recently occurred. The analysis also illustrated the extremely close correlation in the price action between the 1987 stock market and the 1929 stock market, with the implicit conclusion that we were now at the brink of a collapse. I was sick to my stomach when I went home that evening. I realized that I had blown it and that the market was about to crash.”4

Druckenmiller avoided the worst by blowing out of his long position the morning of the crash. Meanwhile, Jones covered his short and went long bonds, expecting the Fed to ease financial conditions. That month he made 62% and became famous.5

January 1988: “Concerned about the future welfare of the world.”

After the crash, Jones did not shy away from publicity. He participated in the January 1988 Barron’s Roundtable and was profiled by the Wall Street Journal who called him the “Quotron Man” (the Quotron was an electronic terminal that provided access to prices and financial information).

The article described his “rock and roll” trading style and eye-popping returns: “last year he had a 200% return, mainly because he dumped stock-index futures just before the crash, then bought heavily while other money managers were still reeling.”

But if Jones was right and 1929 was the historic parallel to 1987, the US was facing another Great Depression. Jones laid out his worries:6

“I’m not as concerned about the direction of the market as I am about the future welfare of the world … will we be able to avoid a worldwide depression like we saw in the early Thirties?”

“The only real operative historical parallel to what we have right now is the Twenties. And the similarities are so striking, so rampant and so numerous that one has to use that as a basis.”

“If you anecdotally go back and read Barron’s, it’s the exact same newsprint with different names and characters in January of 1930. Everyone was optimistic. All the earnings that we’re talking about can disappear overnight, if the stock market makes new lows. The stock market is a leading indicator, and if it starts back down, you could see commerce literally grind to a halt like in the Thirties.”

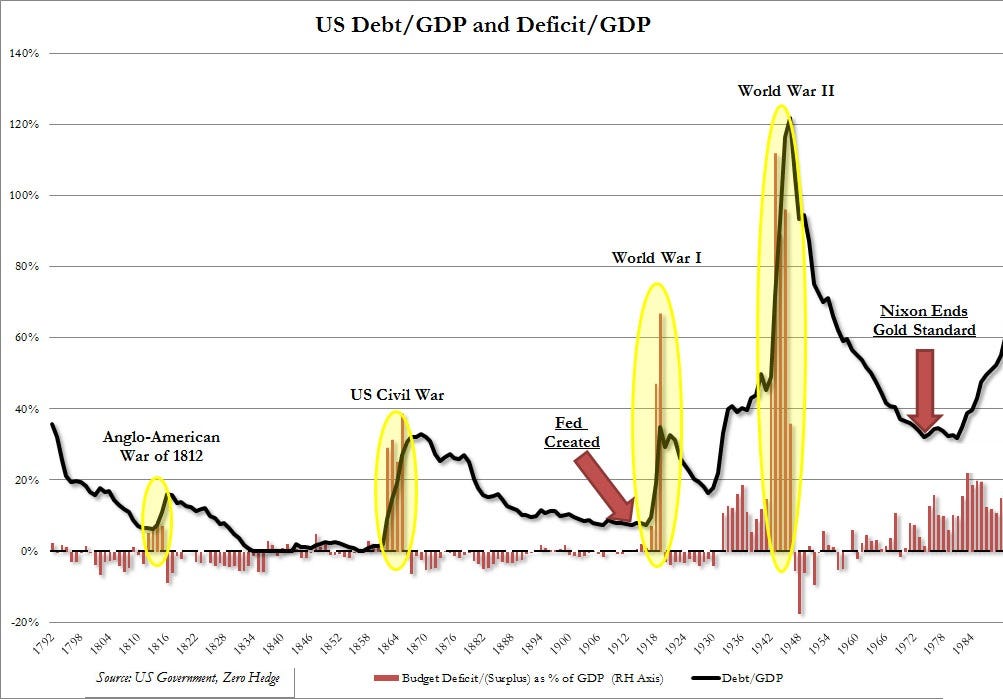

Jones was worried about the lack of “structural shock absorbers.” He pointed to vulnerable corporate balance sheets, the decline in interest rates which had made higher debt levels affordable, the dollar devaluation and “five years of incredible [public] spending orgies.” His argument was that these factors had already boosted the market and asked: “tell me, what policy tool is available?” He concluded: “We’re a debtor nation that acts like a creditor nation.”

Jones was not alone in his pessimistic outlook. After the crash, Robert Shiller published a paper called “Investor Behavior in the October 1987 Stock Market Crash.” He found that the crash of 1929 was an important analogy for investors as they tried to make sense of the 1987 plunge: “comparisons with 1929 were an integral part of the phenomenon. It would be wrong to think that the crash could be understood without reference to the expectation engendered by this historical comparison.”7

Jones balanced his very bearish macro view with a pragmatic tactical stance. He expected a bounce “back to the 2200-2300 area,” similar to the bounce into early 1930. For the second half of the year 1988 he expected new lows and a steep decline to the “1200 area.” His argument was based on market sentiment and positioning:

“Right now […] it’s sold out.” “you’ve got phenomenal insider buy/sell ratios, mutual-fund cash at […] extremes; you’ve got all types of internal indicators that would indicate the market should rally.”

Something like this:

That year, Jones also sat down with Jack Schwager twice for the Market Wizards interview. Schwager noted a change between the two interviews: Jones had started changing his mind.8

Schwager: “Two weeks ago you were very bearish. What made you change your mind?

Jones: “The market didn’t go down. The first thing I do is put my ear to the railroad tracks. I always believe that prices move first and fundamentals come second. One of the things that Tullis [his cotton trading mentor] taught me was the importance of time. When I trade, I don’t just use a price stop, I also use a time stop. If I think a market should break, and it doesn’t, I will often get out even if I am not losing any money. According to the analog model, the market should have gone down – it didn’t. This was the first time during the past three years that we had a serious divergence. I think the strength of the economy is going to delay the stock market break.”

So this is pretty important. Despite the boost in confidence that Jones had received from being right about the crash, he kept his “ears to the railroad track.” When the market wasn’t acting as he expected, when it refused to sell off, he accepted this new and significant information.

His pragmatism prevented an ego response of believing that he market was “wrong.” No, it was Jones who immediately had to change course, adjust his thesis, and basically abandon the now outdated analog model. Notice that he still expected the break, just with a delay. His long-term bearish view was still intact, but he didn’t let it affect his trading.

“I think the financial community was dealt a life-threatening blow on October 19, but they are in shock and don’t realize it.”

“I know from history that credit eventually kills all great societies. “Whether it was the Romans, sixteenth-century Spain, eighteenth-century France, or nineteenth-century Britain. I think we are going to be in for a period of pain.”

We all know where the debt/GDP ratio has gone since…

January 1989: “My job is to get with the flow.”

When Jones sat down for another roundtable discussion in January 1989, the market had recovered steadily. Jones was still a bit skeptical – he didn’t rule out the idea that this was a bear market rally that could break again. But he acknowledged how much the picture had changed. And he was ready to abandon his bearishness if the market told him to do so.

“I think the Fed has done a fantastic job. I really thought last year that there were macroeconomic forces at work that no one would be able to control. And I have learned a lot over the past 12 months, because they have done a good job.”

“I think the big mistake that I made last year […] was not recognizing the difference between 1987 and 1929. In 1929, the dollar value of the U.S. stock market was almost 175% of GNP. Today, it is 50%.”

“Unfortunately, I still believe in the charts first. There are too many instances of 35-40% breaks, followed by 12-16-18 month rallies, where a market did subsequently go back and either double-bottomed or make new lows. Until I see a Dow close significantly above 2240 on a weekly basis – which may be this week – until I see advance/declines turn, I am not going to be invested.”

“Maybe we’re in the nascent stages of a bull market. It is either that, or we are at the top of a bear market.”

“My job is to get with the flow. I will make a forecast, but my job is simply to trade the range.”

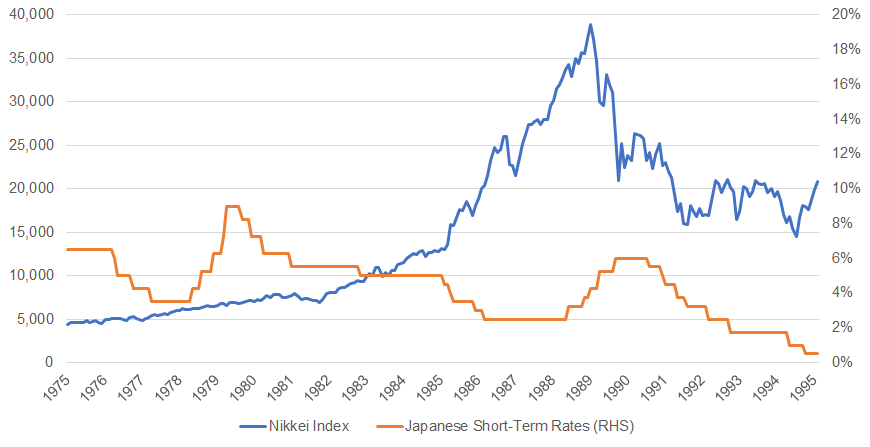

January 1990: “Everything comes back to the Japanese quotient.”

The market continued to make new highs and by January 1990 Jones described it as “seemingly bulletproof.” He noted “a tremendous amount of pessimism,” as indicated by measures like mutual fund cash levels and put-call ratios. At the same time, he was worried about the US economy which he thought was “late in the business cycle” (and would indeed go through a brief recession later that year).

“This time last year, there were many reasons not to be negative on the stock market. Now, I can see an external event that can be very negative. I see internally a number of events that can be very negative.”

He was willing to let the market overrule his bearish bias:

“I would have to see the market take out 2800 and exhibit amazing upside volume before I get too excited about U.S. stocks.”

Interestingly, he also observed that short sellers were doing well in a rallying market, indicating that there was weakness underneath the surface.

“I can have money with four different managers playing the market from the short side – amid a tremendous explosion in the stock market- and they all make money. So, something tells me, intuitively, that something is not right in the landscape.”

Most of all he expected the bursting of the Japanese bubble and feared spillover effects:

“Everything that is being sold on Wall Street today, whether it’s a company, a fund, everything ultimately comes back to the Japanese quotient. I refuse to believe they are not at the base of probably all the asset inflation we have seen.”

“There are a million reasons to be negative on our stock market, but Japan is the biggest factor.”

Following a brief recession and bear market in late 1990, the US market went on to a decade-long bull market that culminated with the dotcom bubble. Fears of a new Great Depression proved to be completely misplaced.

While Jones retained a bearish macro bias for several years, I was impressed that he was ready to abandon the idea of a new Great Depression when the market told him he was wrong. This despite the fact that he had just become wealthy and famous for “calling the crash.”

Meanwhile in Japan…

January 1988: “In particular, I want to be short Japan.”

When the Japanese market started to go parabolic, more than a few people pointed at the forming bubble. George Soros for example was vocally short Japan and was caught wrong-footed when that market held up better than the US in the crash of 1987.9

Jones compared 1980’s Japan to the US of the 1920’s: two rising industrial nations. Two epic stock market bubbles.

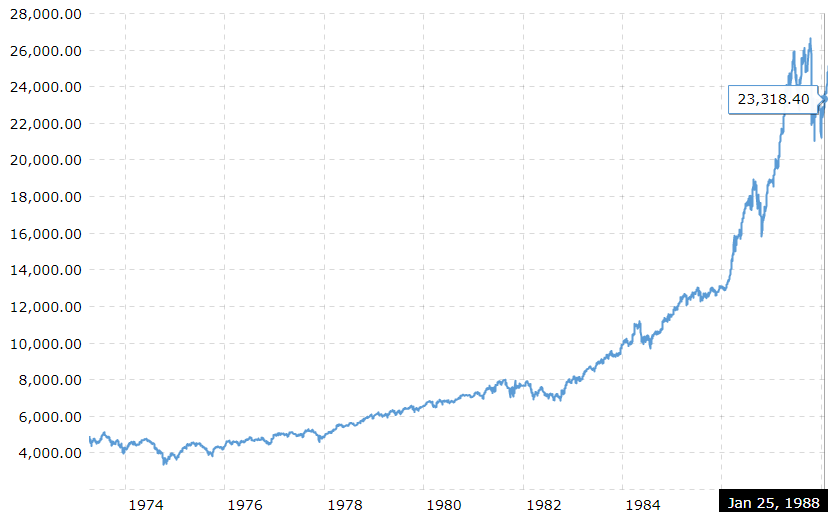

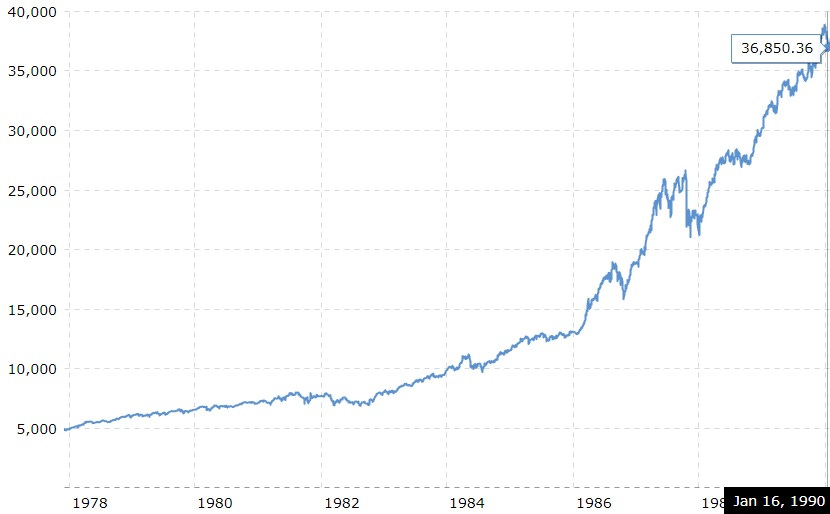

Nikkei Index:

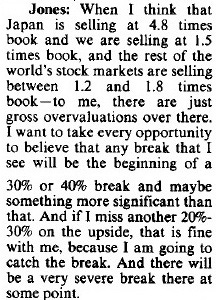

At the 1988 Roundtable he explained:

“In particular, I want to be short Japan. Everyone is so worn out from trying to sell Japan, and yet, the reality of the situation is that – and I hate to use the word – on a ‘fundamental’ basis, it has the greatest downside.”

“Today, the U.S. is analogous to what Great Britain was back in ’29, and Japan is analogous to where the U.S. was. The U.S. market still finished 1929 on a positive note. The biggest correction in 1930, in the world, was in the U.S. stock market.”

At the time there was a catch: the Tokyo market did not have a futures contract, Jones’s preferred trading instrument.

“If they ever start a stock futures market in Tokyo, they’re talking about the sale of all sales.”

January 1989: “Every time that market breaks, I am going to sell it.”

The Nikkei recovered and quickly made new highs. At the 1989 roundtable Jones was humbled:

“Japan was, obviously, the best stock market in 1988. I was 100% wrong.”

“From an intellectual standpoint, during ’88, watching that market [Japan] defy conventional logic was a lesson in humility for me. The great thing about markets is that you learn something new every day.”

Yet he remained confident in his assessment of the fundamentals:

“The Japanese market right now is 127% of GNP. And if there is going to be a problem – if there is going to be an external shock that creates a problem here – it is going to come from Japan.”

He controlled his risk and was very careful about how he expressed this bearish view. Jones had no interest in being steamrolled by an inflating bubble. Instead, he would short only after an initial decline, hoping to catch the sharp decline following the top.

If the market rallied again, he would immediately cover his short. It was an asymmetric bet that became less asymmetric over time if he got stopped out repeatedly:

“I have not been short since it came out of that consolidation range last November. But every time it breaks 5%, I will sell it. I will probably try to market-time it, and risk 2-3% of my portfolio. And it will probably cost me another 4-6%. But it is going to break. I will catch it, and I will get paid 25% or 30% or 35%. That is my function, to try to get with it.”

“Being short in Japan in 1988 probably cost my fund about 4%.”

He also kept close tabs on the market’s ecosystem. When in September 1988 index futures were first traded, Jones immediately visited the country. He watched trading live at one of the brokerage houses and noted that trading volumes had already eclipsed that of the US market prior to the crash.

January 1990: “I am extremely negative right now.”

The Nikkei went parabolic in 1989 but experienced a small decline in January 1990.

At the roundtable Jones was a raging bear:

“[Japan] went parabolic. Its rate of acceleration was as great as any other period in the history of the stock market.”

“The fact that it has actually doubled without anything even approaching a 6% decline makes it all that much more of a candidate to ultimately burst.”

“You have the potential for that market to decline 20% or 30% in a rapidly accelerating fashion.”

He admitted that he had been stalking this bubble for some time:

“I first started getting bearish on it when it was around 24,000, and now it now is 37,500. So even if it declined 40%, I would still be completely wrong as far as that forecast went.”

“The sustainability of the bubble, though, is directly dependent on a continual progression in prices.”

He wasn’t the only bear. The market advance had become increasingly narrow and raised many eyebrows:

Jim Rogers: “When you look at the advance/decline there, the market has gone up 4,000 or 5,000 on very few stocks. They drove up a few very big stocks.”

Felix Zulauf: “That advance/decline line goes down for 10 years.”

Jones: “When you see that kind of chart pattern – I don’t care what it is – it is a signal to watch out for the terminal point in that particular market.”

Playing the Player

Jones’s bearishness was supported by a new element. He had familiarized himself with the positioning and incentives of the major players in the Japanese market. He had formed a thesis of how these key players would react if the market weakness continued.

“Look at the breakdown of assets held by Tokkin funds and/or insurance companies and/or investment trust. In the past seven years, their holdings of stocks have almost tripled, going from 14% to over 52%. Their bogey is 8%. They have to get 8% in some fashion.”

“There was a euphoria building up in that market because of the perceived January effect … And you have now started out in the beginning of January with a 3.7% decline, which is the worst two-week performance in Japan since the 1947 era. Now, you are looking at a situation where they are down 4% in the first two weeks of the year. And, they have an alternative that they haven’t seen since the early 1980s. That is, 7.25% short-term rates.”

“So here you have a very compelling reason for the Japanese stock market to decline – much in the same way that portfolio insurance brought down the market in the U.S. in 1987. Every day the market does not advance, and particularly, every day that it declines, it becomes that much more compelling for a manager to shift his assets from stocks. “So here we are, at the beginning of the year, and I posit that, from a fundamental standpoint, there’s probably the greatest opportunity for a reversal of that flow that has ever existed.”

Indeed, the BOJ had raised rates and the bubble that Jones had been stalking for years was starting to unwind at long last. Today the Nikkei stands at around 30,000. Still below the 1990 all-time high.

May 1990: “Past the Peak.”

Jones met with Barron’s for a follow-up interview. He was up 30% for the year. When Barron’s called his prediction on Japan a home run, he noted that he had been making the same prediction in both 1988 and 1989. Jones described the Japanese top as a peak like “1929 or 1966” that would not be exceeded for another 25 years. In his view, the market had “a long way to go on the downside” and little “real liquidation” had taken place yet.10

Despite this extremely bearish long-term stance, he was actually long Japan at the time of the interview! He believed the shorts were getting too aggressive - “too many U.S. buyers of puts anticipating an easy money play for the market to accommodate them.”

I’m not advocating anyone try this at home. But it’s another example of just how agile a trader he is.

“My investment strategy springs from developing a fundamental view of a particular market. Under- or overvaluation is only part of the battle. The key thing is to be able to time one’s entry into a position at the precise moment when the market is about to move in your favor.”

“If you put a gun to my head and ask me to choose between fundamental and technical analysis, I would take the technical every time.”

Takeaways

I hope I was able to shed some light on Jones’s process, on how he made decisions in volatile and uncertain conditions. I will close out with a few observations on his principles.

“Don’t be a hero. Don’t have an ego.”

“Ego is the single most destructive force you can confront in business. I treat every trade as a business decision. You have to be sure you have the discipline to get out of a losing trade.”

“Who cares where I am long from. That has no relevance to whether the market environment is bullish or bearish right now, or to the risk/reward balance of a long position at that moment.”

Jones had found one of the most enticing macro ideas: the chance to short a bursting bubble. This is reminiscent of doomsday narratives that are so powerful they continue to spawn religious and financial cults. Let me illustrate the appeal: the world is corrupt (a bubble has formed) and those who are devout (have put on the right trade) will be rewarded while those who have sinned (made effortless money with careless risk-taking) will be punished. You can get rich and feel good about it because you are spreading a message of divine justice!

It’s easy to adopt this narrative and proceed to blow yourself up going short because you were early or misdiagnosed a bubble. The beauty of this story is that Jones did both, he was early on Japan and wrong on the US being in a bubble. And yet he managed to survive and thrive. Because at his core, he was a pragmatist who did not get overly emotionally attached to the big idea.

Jones remained open to new information and humble about what the market could teach him. He didn’t complain about how irrational the market was. Jones simply observed what happened and adjusted his posture when things did not go as planned. Ultimately, his job was to “go with the flow.” In the words of Jesse Livermore: “the only thing to do when a man is wrong is to be right by ceasing to be wrong.”

Risk management.

“Risk control is the most important thing in trading.”

“The most important rule of trading is to play great defense.”

“First of all, never play macho man with the market. Second, never overtrade.”

“If I have positions going against me, I get right out.”11

I would argue that Jones’s risk control, his ability to survive when being wrong, was as important as identifying the idea in the first place.

The following is a quote from a risk control memo Jones sent to his traders in 1994. In the memo he outlined rules on position sizing and measures to be implemented in a drawdown:

“No trader can maintain quality performance over time without a systematic approach to risk-control in conjunction with risk-control rules that will not be violated at anytime.”

The lure of history.

This episode illustrates how deceptive it can be to rely on historical analogies which paint a compelling narrative. In 1987, Jones made a lot of money with his overlay chart even though the parallel to 1929 turned out to be flat out wrong. John Templeton said the four most expensive words in the English language were "this time it’s different." Some things don’t change: the laws of physics, human nature. And while they continue to create boom bust cycles, a lot of other factors are changing dramatically. There is value in knowing history, but it is no substitute for thinking deeply about the present.

Playing the cards and the players.

Was Jones right in his assessment of the Japanese institutions or had the bubble just run its course? Did it just implode under the weight of its own inflated expectations? I do not know. But it is notable that Jones placed such emphasis on understanding and knowing the players. When futures started trading in Japan, he immediately visited. He watched the New Year’s ceremony at the Tokyo stock exchange. If he was going to make a big bet, he wanted an intimate understanding of this ecosystem. He cared about sentiment, incentives, biases, positioning. He assembled a mosaic of macro and fundamental pieces and tried to put himself into the shoes of the players whose actions would most impact the outcome. Then he patiently waited for his fat pitch.

Bruce Kovner, who rarely voiced his views in public, once said: “I don't want to be defending a position or worried about looking good.”

How lucky we are that Jones thought differently:

“I avoid letting my trading opinions be influenced by comments I may have made on the record about a market.”

Cotton trader Eli Tullis said about Jones: "You could see him start the day a bull and finish it a bear." And in a 1997, another market observer noted: “Time and again I’ve heard traders say, ‘You can always see Jones coming, but you can never see him going.’”

That’s something to keep in mind when you hear Jones comment on markets. Whatever his stance today, he has the mental flexibility to go with the flow tomorrow.

“You guys [Barron’s] talk about buying stocks and holding them for the long run. I’m flipping $300 million every four or five days in the futures markets, because I’m a product of the day. I’m a consumer at heart, because that’s the way I was raised.”

Market Wizards, Jack Schwager

“Trader With a Hot Hand,” Barron’s, June 1987; see also: Trader With a Hot Hand

Ibid

The New Market Wizards, Jack Schwager

Market Wizards

Barron’s Roundtable, January 1988

“Investor Behavior in the 1987 Stock Market Crash,” Robert Shiller, NBER Working Paper No. 2446

Market Wizards

“This Time the Turning Point Has Been Reached,” George Soros, Financial Times, October 14, 1987

“Past the Peak,” Barron’s, May 1990

Market Wizards

Fantastic work!