What if? Warren E. Buffett, An Alternate History

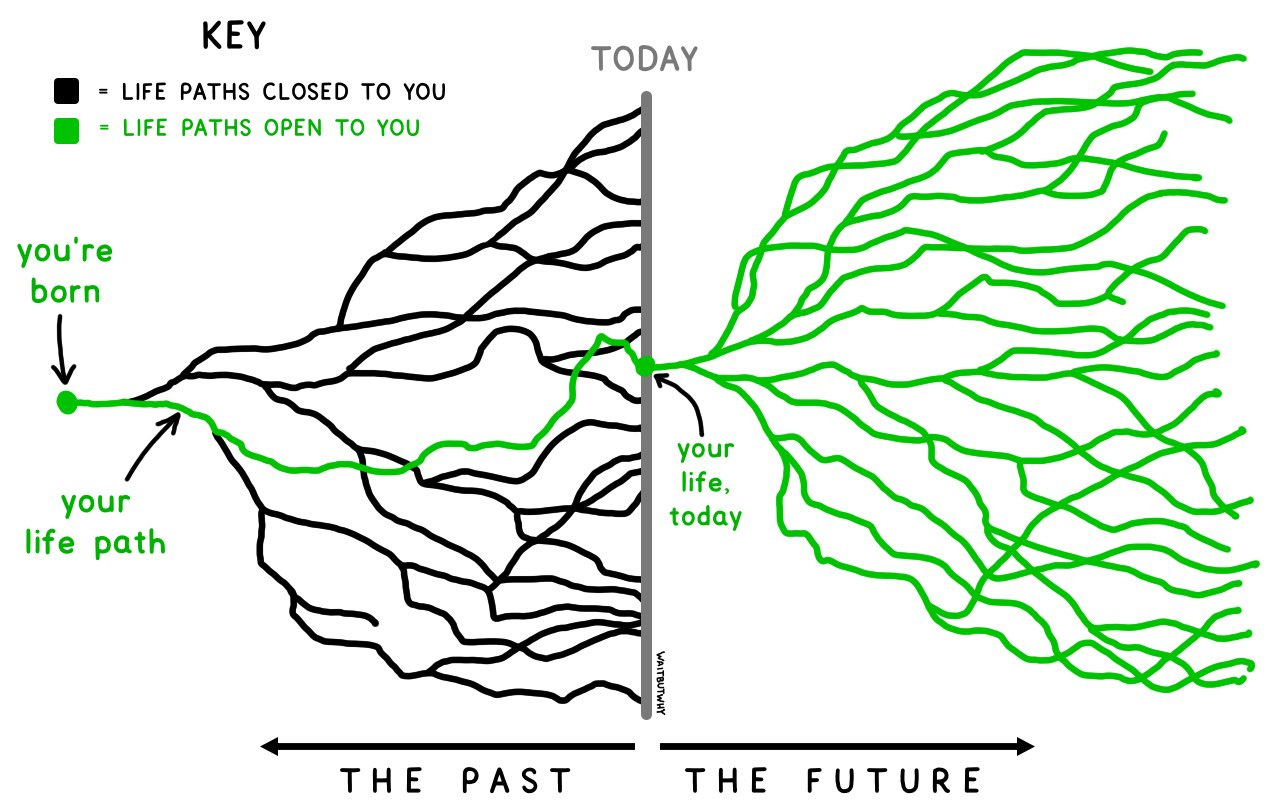

"We are born a thousand men and die as one." (HBO's Industry, but also Heidegger)

Hello everyone,

In 2022, Todd Combs asked Charlie Munger an interesting question:

If you hadn't met Warren, what do you think you would have been doing in life?

Munger answered he would have continued his law practice but would still have found his way into full-time investing. (Reginald Lewis went through the same transition from advisor to principal).

Asking ‘What if?’ can lead us down interesting paths. I find it particularly compelling for Buffett given his long and well-documented career involving countless decisions and characters. Remove just a few key elements and the arc of his life could have bent in a very different direction. Or, as Munger likes to say, all of life is just “one damn relatedness after another.”

With Berkshire’s annual meeting around the corner, I had some fun imagining how close Buffett came to living a different life. What else could have happened?

In The Undoing Project, Daniel Kahneman outlined biases of imagination, what he called the ‘rules of undoing’:

In undoing some event, the mind tended to remove whatever felt surprising or unexpected—which was different from saying that it was obeying the rules of probability. It was a tool for making sense of a world of infinite possibilities by reducing them.

The more items there were to undo in order to create some alternative reality, the less likely the mind was to undo them. People seemed less likely to undo someone being killed by a massive earthquake than they were to undo a person’s being killed by a bolt of lightning, because undoing the earthquake required them to undo all the earthquake had done.

Another, related, rule was that “an event becomes gradually less changeable as it recedes into the past.” With the passage of time, the consequences of any event accumulated, and left more to undo. And the more there is to undo, the less likely the mind is to even try. — The Undoing Project

I found this to be true when I kept gravitating to key turning points in his life. It’s much harder to imagine seemingly arbitrary alternate timelines. Buffett, who serves in the Korean War and returns with a different outlook on life, disinterested in markets; or with a mental health issue, unable to focus or stomach volatility as he had before. Buffett, who barely survives an accident, retires early, and devotes his time to family and charity. Buffett, whose marriage ends early and who leaves Omaha to escape the haunting memories.

It feels much easier to remove people or decisions from the story we know, than to add new elements which can open up an infinite number of new threads.

What if he had never met Charlie Munger? No acquisition See’s Candy for starters.

Charlie was the one that said, “For God’s sakes, Warren, write the check.”

And as a result perhaps no investment in Coca-Cola.

But Buffett also used to call Munger the “abominable no-man” for the latter one’s tendency to shoot down ideas. Would Buffett have made more mistakes without Munger? Probably. But which? This may have been just as important a factor in Berkshire’s success, but it doesn’t offer a narrative to attach to. Consistent with Kahneman’s rules, the mind strains against these open-ended scenarios. So just keep in mind that this little thought experiment is inevitably biased.

Take another missed connection: what if young Buffett showed up at GEICO’s offices only to find the doors locked? No revealing conversation with Lorimer Davidson. No in-depth understanding of GEICO. I think Buffett would have been determined enough to try again. But what if…

Or consider his first acquisition of an insurance operation, National Indemnity. The fact that it was purchased for Berkshire and not for his investment partnership has been framed as a kind of original sin. Buffett wrote about it in 2014:

Early in 1967, I had Berkshire pay $8.6 million to buy National Indemnity … a small but promising Omaha-based insurer. Why did I purchase NICO for Berkshire rather than for BPL [Buffett Partnership]? I’ve had 48 years to think about that question, and I’ve yet to come up with a good answer. I simply made a colossal mistake.

If BPL had been the purchaser, my partners and I would have owned 100% of a fine business, destined to form the base for building the company Berkshire has become. Moreover, our growth would not have been impeded for nearly two decades by the unproductive funds imprisoned in the textile operation. Finally, our subsequent acquisitions would have been owned in their entirety by my partners and me rather than being 39%-owned by the legacy shareholders of Berkshire, to whom we had no obligation.

Despite these facts staring me in the face, I opted to marry 100% of an excellent business (NICO) to a 61%-owned terrible business (Berkshire Hathaway), a decision that eventually diverted $100 billion or so from BPL partners to a collection of strangers.

In The Snowball, Munger commented that Buffett would have been a lot richer “if he hadn’t been carrying all those shareholders.” In the partnership he was paid a share of the profits compared to a modest salary at Berkshire. But, Munger reflected, Buffett “was never just rawly competitive with no ethics.”

Buffett “wanted to live life a certain way, and it gave him a public record and a public platform. And I would argue that Warren’s life has worked out better this way.”

I agree. But what if…

What if?

I have more ideas for a future post. If you have your own ideas on how Buffett and Munger’s lives could have played out differently, email me or ping me on Twitter.

The Market Wizard. What if he’d never picked up Graham’s books?

The Bostonian. What if he had gone to Harvard?

The Family Office. What if the National Guard had allowed Buffett to move?

The Successor. What if Buffett had remained in New York?

The Dempster Dumpster. What if Buffett had never met Munger?

Graham’s Final Lesson.